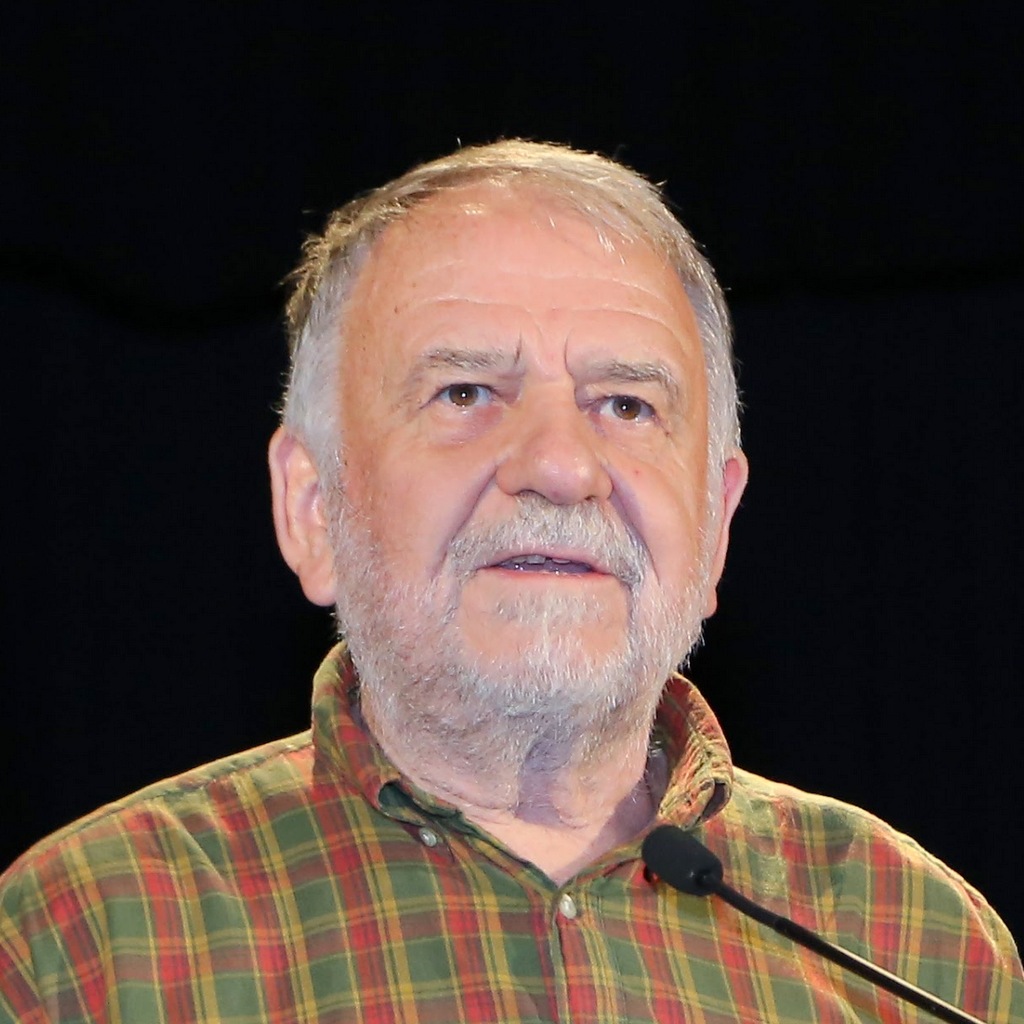

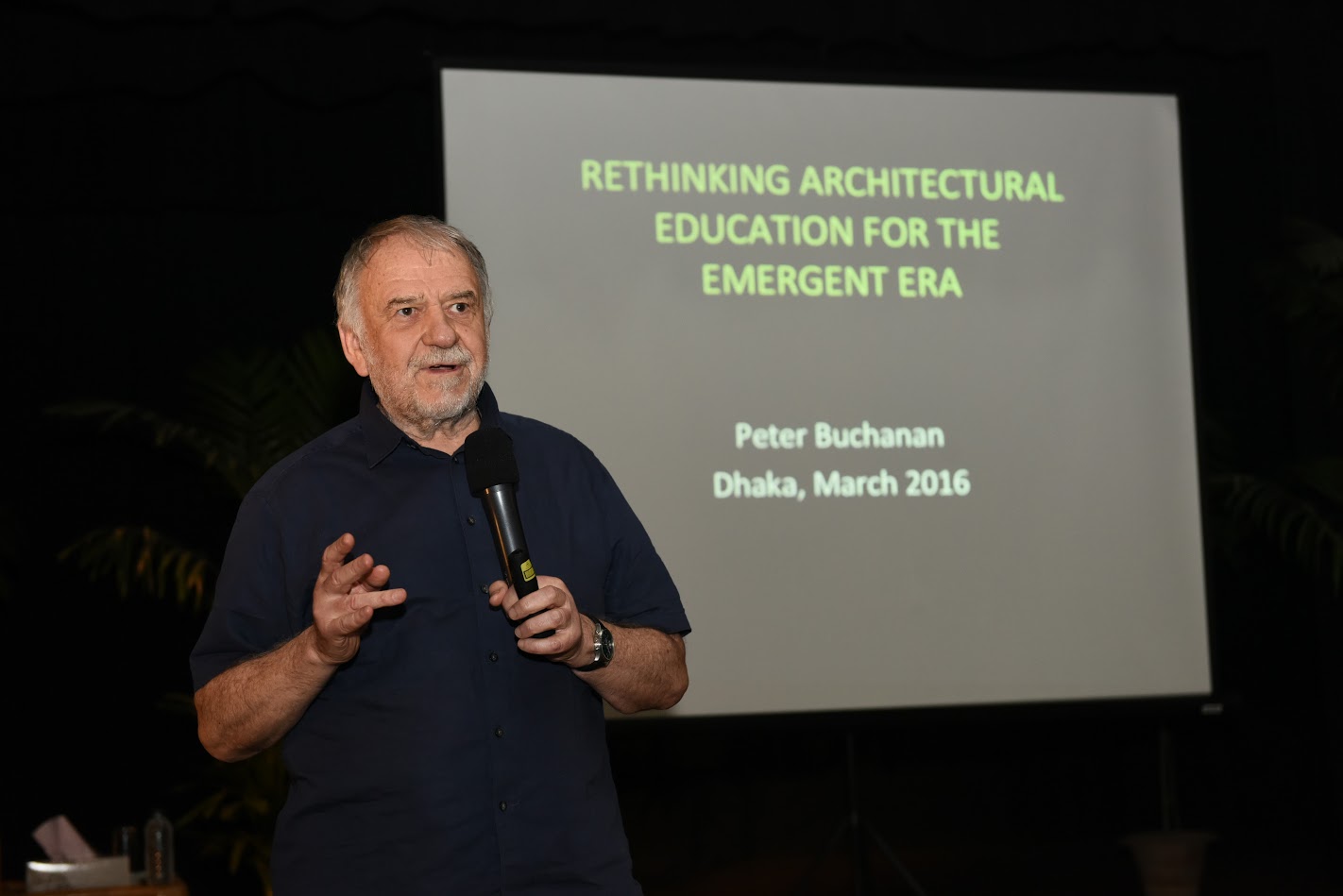

Peter Buchanan: Rethinking Architectural Education for the Emergent Era

Thu 24 Mar - Thu 24 Mar' 16

Peter Buchanan says he is not an academic, but he is an architect-urbanist who writes, and now teaches at the London School of Architecture. His impression is that the quality of schools and teaching within them varies considerably, and the best schools are neither the famous ones nor in likely locations. (Often a few individuals lift an otherwise ordinary school.)

He said, schools were slow to update and pace up with the practice. Only a few new schools are emerging to cope up with this crisis, like at the LSA, all students are working part-time, all faculties are practicing architects and students pay their tuition fees from the money they earn from working. There will be no tenure and the faculty lineup will always be renewed. Sometimes a teaching position may be taken by a practice rather than an individual. The school has no permanent base and will move between London’s boroughs and work in collaboration with their municipalities on local, reality-based projects.

There were some consistent comments about architecture schools, like schools not providing a proper grounding in architecture, particularly its technical and construction aspects. This is certainly true of some schools, particularly the ‘elite’; but much less so of those the elite dismiss as ploddingly “provincial”. Tellingly, tutors at elite schools send their children to “provincial” schools, expressly so as to get a proper grounding in construction. Students complain of poor design tuition – particularly by academic teachers who themselves cannot design. Having fallen far behind the leading-edge of practice this presented a major challenge, not least in giving students access to the level of consultants that such practices collaborate with. Also there is a lack of comprehensive and coherent curriculum, and the fact that the studio emphasises concept rather than craft. And students are pressured to quickly produce concepts, a misunderstanding of the creative process: concepts should emerge rather than be imposed.

Problems are compounded by the drive for architectural education to be more academic, hence the rise of theory with many posts going to PhDs at the expense of architects being experienced in design and construction

Theory has become a self-referential equivalent of medieval Scholasticism – a major reason academe has fallen behind practice. Although issues such as sustainability became more pressing, they tend to remain marginal add-ons and restricted to objective issues of ecology and technology. Whereas many professors privately confide the view that architectural education does not belong in universities.

Some of the big changes are underway, and an architectural curriculum adequate to the emerging epoch is evident. For architectural education to catch up with where practice is now, challenging as that is, falls far short of what is required. The massive changes we are undergoing require application of new knowledge and new modes of thinking that are more inclusive and integrative. Most especially we need to adopt a ‘Meta Theory’ that both charts the horizontal relationships between our exploded fields of specialist knowledge and included a vertical dimension giving us an elevated perspective that helps us apply this knowledge wisely. Such meta theories have long been available but, although powerfully relevant to it, have been ignored by architecture – the one field where all knowledge is synthesised.

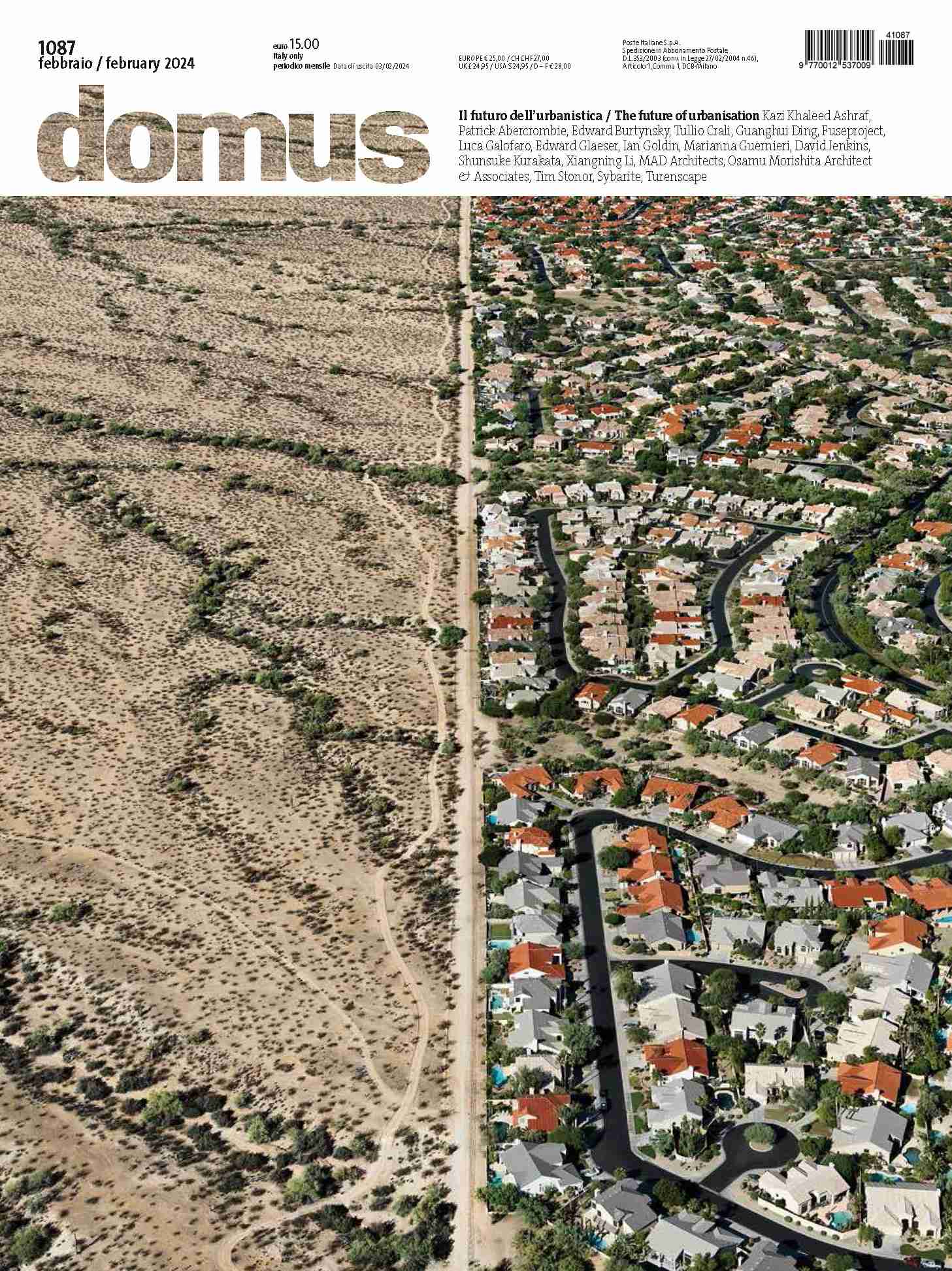

The changes afoot and these meta theories will even provoke a radical rethinking the very purposes of almost all facets of life, including of architecture and urbanism.

We need to look far, stretch beyond our comfortable cocoon. “Whoever discovered water, it wasn’t the fish” – This was how Marshall McLuhan explained our blindness to the degree to which we are shaped by our omnipresent communication media. But something very similar applies to architecture, to which our relationship is so intimate and sustaining that we are relatively unaware of it. This is true even of architects and architectural academics. A deeper understanding of the purposes of architecture and design is necessary to help formulate the most elevated and empowering vision of them relevant to the emergent epoch. This is vital to achieving sustainability, inspiring change, and revitalising architectural education. Sustainability cannot be achieved by objective means alone, such as technology and ecology, vitally important as these are.

We are complex, cultural beings exiled from nature. Architecture starts in part as compensation for this exile from Eden, creating an independent human world. It originates in imagination and fantasy as much as shelter and function. These two factors, spatialisation of the psyche and compensation for separation, have driven the elaboration of culture and architecture – including the great glories in buildings, gardens and urban set pieces. Like culture, architecture is a largely unconscious compensation for our exile from Eden. When architecture loses its cultural dimension it becomes functional and abstract, alienating us and leaving us homeless because now outside this web of relationships. Returning this sense of connectedness is fundamental to advancing sustainability. It is time to reconnect – with each other and our deep selves, with nature and our built environment: to come home again.

The current state of architecture is either a theory dominant postmodernism or a computer generated spaghetty. Peter Eisenman’s City of Culture, Santiago de Compostela in Spain for example, is an extravagant absurdity of illustrating theory at the expense of any other reality. And then we have the pandemic attempt of the computer generated forms, which makes any form possible, raising the question: which forms are relevant to architecture and our relationship with it? Buildings as products of surrendering uncritically to softwares.

We need to rethink the whole curriculum and method of teaching at the schools involving Multiculturalism and Spiral Dynamics. An example is the All Quadrant architectural curriculum: At the core, drawing on in pragmatic fashion and synthesising all these disparate fields of knowledge is the design studio and its associated research.

Publication