Written by Shiny Varghese |

Updated: December 17, 2021 9:40:48 am

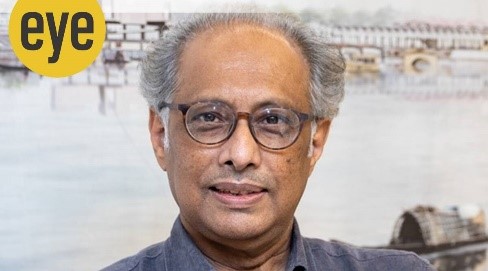

Muzharul Islam, the first professionally trained architect in Bangladesh, set the tone for how the fluvial landscape would be measured, both in its aesthetic and urban planning ideas. His work is still a primer in understanding “modernity in Bengal”. Today, as young architects receive international acclaim, what are the challenges for a city and the practice of architecture. Architect-urbanist Kazi Khaleed Ashraf, 62, director-general, Bengal Institute for Architecture, Landscapes and Settlements, Dhaka, talks about the landscape imagination, the essence of nation-building and evaluating architecture through its locational ethics.

Edited excerpts:

How did the late Muzharul Islam influence the way architects of the time viewed the city and their own future?

Muzharul Islam was quite sure that he was not interested in singular, stunning buildings. In the late 1960s, he was talking about the larger aspect of architecture, its social and urban dimensions. Architects of that time were mostly engaged in commercial enterprises, they were hardly concerned with the landscape of the city or the future of communities. Islam amplified the social and nation-building role of architecture. He spoke about the need for architects to engage with regional planning, or three-dimensional physical planning, in short, to need to deal with the larger scale. What I am doing today is an inheritance of Islam’s call for the larger role of architecture. I often say in the present context in Dhaka, architects are doing stunning buildings, but the city is going to hell. There is a fissure in how we do things, and I wish to address that by working with the fabric of the city.

Muzharul Islam, College of Fine Arts, Dhaka. Photo Saif Ul Haque (Courtesy Bengal Institute for Architecture, Landscapes and Settlements, Dhaka)

In the past, you’ve written about how India’s Achyut Kanvinde and Islam were almost working in parallel, in terms of their values of architecture as a nation-building exercise. Could you elaborate?

Both Achyut Kanvinde and Islam’s notions of modern architecture involved the social, and in the context of the 1950s and ’60s, the demands and requirements of the new nation-state. Not just buildings for their own aesthetic gratification, but how they impacted society. Just as Kanvinde was sent by (India’s first prime minister Jawaharlal) Nehru to Harvard (University, the US) for training, to return and design the various IITs, Islam was trained in Oregon (University) and later, at Yale, to be involved in the design of many institutions. With his friend, American architect Stanley Tigerman, he designed five polytechnic institutes and created a landmark manual for building in Bangladesh. We often forget that these architects were working in a certain intellectual and motivational vacuum as far as architecture was concerned. Their buildings, therefore, participated beyond building-making, into establishing a new culture of living, working and thinking.

Like Nehru, Islam too got international architects such as Louis Kahn and Paul Rudolph, among others, to come and work in Bangladesh. How has that influenced the way architecture was done in the country? For instance, in India, we still carry the Le Corbusier legacy in so many ways.

Nehru invited Corbusier to India to hit Indians on the head, as he himself said. It was not quite like that in Bangladesh, or East Pakistan, then. Islam was simply an architect, he did not invite Kahn, Rudolph, and others directly, but was instrumental in getting them to Bangladesh. This was not so much to hit Bengalis on their head, but to build up an international level of practice in an architecturally vacuous situation. It’s also known that Islam was first approached to design the parliament complex in Dhaka, but he suggested getting Kahn. Now that’s a sacrifice for nation-building! With such stalwarts working in Bangladesh, the beginning was already robust, the discourse was already of a high calibre. Of course, then, and certainly now, you could critique the work for advancing into other directions, but the die was cast for a distinctive architectural culture and language.

Anna Heringer and Eike Roswag-Kleine, METI Handmade School, Rudrapur. Photo credit Anna Heringer office (Courtesy Bengal Institute for Architecture, Landscapes and Settlements, Dhaka)

Islam’s Public Library (now Dhaka University Library) and the Dhaka Art College was a definitive change at the time (from the Mughal and British times), even if it was during the Pakistani period. In these buildings, politics and aesthetics intersect in an interesting way. Could you talk about it?

Working in the 1950s, Islam’s quandary was what should be the basis of his work. The immediate past could not be relied upon, that basically involved the brandishing of colonial culture. He decried both the stigma of colonialism and some of the dark aspects of what goes as tradition. Modern architecture, with its clean non-referential language, was preferable to him to bypass that quandary. His architecture was not an aesthetical enterprise, but an ethical one in which a minimal, decent architecture was able to cater to the diverse and emerging needs of a new nation. I stress the word ‘decent’, a term he used frequently. What I think he meant was a kind of architecture devoid of flamboyance but respectful of the grace and poise of Bengali life of that time.

In recent times, Bangladesh architecture seems to be thriving on new energy, and buildings by Kashef and others are making waves internationally. How is this different from the ‘new energy’ of building a new nation, 50 years ago?

The new energy 50 years ago that you speak of was articulated by many foreign architects and Muzharul Islam as the lone Bengali figure. The new energy of that time literally involved nation-building, providing the institutional facilities for societies entering a new economic realm. The position was pragmatic and utilitarian for the most part. The new wave now that you speak of represents a new depth and content. Combining the ethics of ecology and a commitment to communities, these fascinating projects are bringing in a new modality to architectural practice which also discards the egoistic pretense associated with conventional practices. One quick point, in Bangladesh, the ethics of ecology involves the landscape that, in turn, immediately ushers in the waters. Architects in Bangladesh must confront the waters, and this is seen in a number of innovative and experimental works.

Saif Ul Haque, Arcadia School, South Kanarchor. Photo Aga Khan Trust for Culture, Sandro di Carlo Darsa (Courtesy Bengal Institute for Architecture, Landscapes and Settlements, Dhaka)

Saif Ul Haque, Arcadia School, South Kanarchor. Photo Aga Khan Trust for Culture, Sandro di Carlo Darsa (Courtesy Bengal Institute for Architecture, Landscapes and Settlements, Dhaka)

Critic Kenneth Frampton’s idea of architectural regionalism is much in currency for its focus on context and customs of the region. How is Bangladesh faring in this?

Frampton’s notion of critical regionalism was deeply impactful in the discourse and practice of architecture since the 1980s. An aspect of it influenced the theme of identity in architecture as well. We have moved on to new urgencies now such as sustainability and ecological planning, but the earlier idea still haunts us. It has certainly established a locational ethics with which to assess and evaluate a work of architecture. I am very interested in locational ethics in how a work of architecture ‘takes place’ and evolves from or synchronises with a location. More than ‘what is architecture’, I have always been interested in ‘where is architecture’. You see, no matter what, we are always somewhere. You, I, and even a building. What does that mean? In some of my writings, I have tried to theorise it, and have used it to identify insightful work in Bangladesh. I might add, this is not quite about cultural nationalism.

Kahn called the Bengal delta the architecture of the land. And he managed the confrontation of land and water quite well in his Assembly design. What are the ways that architects today live through this land-water mesh?

I would not use the term confrontation, rather its opposite. Beyond his magnificent robust buildings, Kahn’s ensemble showed how one works and lives with water, and how his work became a deeply poetic response to how you say: the land-water mesh. He may be the first modern architect who incorporated water with such depth in the fabric of architecture, in fact, water was the turning point. What he identified in Bangladesh, very perceptively, was that in the Bengal delta, one needs to be an ‘architect of the land’, that is, even before the articulation of building-form, one needs to consider the modulation and rearrangement of land. Any rearrangement of the land would immediately mean working with water. What Kahn may have arrived at intuitively now suggests a deep orientation in landscape imagination. And this is what is being addressed in some of the works of Kashef Mahboob Chowdhury, Saif Ul Haque, (Khondaker) Hasibul Kabir, and others.

Your 2017 exhibition, ‘Bengal Stream’, travelled internationally and was very well received. What are you most proud of and what aspects of a new Bangladesh did the world see?

The fact that it was well received and continues to draw attention is what we are happy about. The exhibition was organised by the Swiss Architecture Museum and Bengal Institute. This was the first time the Europeans saw the new wave of architecture from Bangladesh, and learnt about the passion of some architects in a variety of projects, from community and landscape-motivated work, to restoration of boats and amphibious architecture. For a small country, the diversity of work is quite incredible. But I will also repeat myself: locational ethics is an underlying theme in most of the work.

Chetana, an architecture study group, initiated by Islam, was about creating new ideas and identities for the country. The Bengal Institute, which you head, has been instrumental in working in smaller towns. What are your new findings and how have people responded to your ideas?

Chetana was initiated in the 1980s with the intention of restoring architecture from the circle of commerce to the core of culture, and establishing a productive linkage with history. If you speak about the identity of the country, it is most fundamentally fluvial and deltaic. The Bengal Institute is interested in cities and settlements, from the metropolitan to what you call, the small. It’s interested in their future, interested in how they intersect with the landscape. In the Bengal Delta, such a landscape is a terraqueous one. So, at the foundation of it all — how we must dwell in the Delta — the dynamics of water, its flow and overflow. We are trying to establish a theorem for living energetically and harmoniously with that fluvial landscape.

Originally published in The Indian Express on 16th December, 2021