Kahn’s Journey to the National Assembly Building

by Shamsul Wares

Published in The Daily Star on 1st March, 2021

What Einstein’s E=mc2 is for physicists, Louis I Kahn’s “Silence and Light” is for architects. Kahn’s lecture on “Silence and Light” in 1969, five years before his death, was the recapitulation of his collective thoughts based on metaphysical reasoning that he considered a key to his point of view, applicable to all works of art, including architecture.

Louis I Kahn transformed as an architect when he built his first major design, the Yale University Art Gallery (1951-53) in New Haven, Connecticut. He received the commission while he was a resident scholar at the American Academy in Rome (1950-51). During that period, after visiting the ruins of ancient buildings in Italy, Greece and Egypt, he changed his approach to design and adopted a design principle based on the basics. Until that time, Kahn’s mind was oscillating between two different streams of architectural thoughts. One was what he had learned at the University of Pennsylvania (1920-24), where the Ecole des Beaux Arts teaching method was based on French Neo-Classicism, incorporating elements from the Gothic and the Renaissance. The other stream was “Modernism” that pursued “order” and “universal” and based architecture on the abstract principles of design and rejected tradition and ornamentation. Creating new forms of expression and a unique aesthetic, Modernism emphasised function, simplicity and rationality. Alberti (1404-72) defined two conditions for architects: architect as a thinking man (homo cogitans) and architect as a craftsman (homo faber). Kahn was attracted to both conditions.

After graduation in 1924, Kahn gradually embraced Modernism because it contained the substance of liberalism and humanism. Although Kahn was experimenting with various aspects of Modernism, he was never content. Kahn realised why Cezanne, who participated in the Impressionists’ exhibition, soon withdrew himself from there — he was not convinced by the Impressionists’ way of depicting a fleeting moment by focusing on changing light. Cezanne felt that the Impressionists were unable to capture the order and permanence of nature itself and, instead, became more interested in the permanent architectural qualities of the landscape. Like Cezanne, Kahn was also troubled by the visual lightness and floating character of the modernist architecture and instead was craving for an architecture that could bring back the sense of stability, permanence, and timelessness without losing the modernist abstract principles. With the design of the Yale Art Gallery, Kahn was able to establish an “alternate modernism” and that was the beginning of his transformation.

With the Yale Art Gallery, Kahn’s works testify to a conviction in three entities: The Pantheon, the Pyramid and the Holocaust. For Kahn, the Pantheon was a place for contemplation, a place to transcend life. He realised in the Pantheon how the basic principles of architecture remained in the service of the ethical, moral and aesthetic spirit of human existence and how it transmitted the sense of wonder. With its oculus and the giant dome, the Pantheon epitomised a search for the divine that Kahn believed had always been and would always be. The Pyramid always fascinated Kahn for its primordial power, strong geometry, and enormous presence in the arid landscape with a sense of eternity. Human dignity was also of utmost concern to Kahn; he consistently aspired to enable his architecture in the reconstruction of the human dignity that was reduced to nothing during the Holocaust.

Kahn found primarily concrete and brick as his chosen materials in order to express the greatness of man-made space. The triangular stair within a cylindrical shaft in Yale Art Gallery (1951-53), Central Atrium in Exeter Library (1965-72) and the Assembly Chamber in Dhaka with a concrete paraboloid roof (1962-74) all belong to the Pantheon. In all these projects, Kahn reworked the oculus (the eye towards God) of the Pantheon to establish its timeless essence and relevance. The Pantheon has a grand illusive interior, whereas the Pyramid has a magnificent exterior. Kahn gained both in the Assembly Building in Dhaka, his most beautiful and glorious creation.

Kahn exercised his concept of ‘served and servant’ spaces first in the design of the Yale Art Gallery, and more explicitly in the Assembly Building in Dhaka. The core function of the Assembly Building is the Assembly Chamber, placed at the centre in a regular octagonal enclosure, lit by natural light from the roof. Eight wedge-shaped light wells are inserted within the octagon to provide natural light to the adjacent spaces on three sides of each of the light wells. Eight building blocks as servant spaces are placed around the central Assembly Chamber. Among them are the presidential entrance on the north, rooms for ministers on the west, dining and meeting room on the east, a mosque on the south and four rectangular office wings inserted among these conspicuous elements. The eight-storey high, ring-shaped ambulatory, extending from the ground floor to the ceiling, circles around the centrally located Assembly Chamber. The ambulatory is also treated as an urban street with light posts. The whole arrangement is articulated in a centripetal order towards the central chamber. As the intermediate zone, the ambulatory separates as well as unites the served and the servant spaces. Striped-configured glass blocks in the ribbed roof of the lofty ambulatory provide natural light. Instead of brise-soleil that was used by Le Corbusier in India to reduce heat, Kahn used thick walls, atriums and light wells in a subtle way to reduce heat entering the building.

In the end, fulfilling all functional requirements, the Assembly Building looks more like a giant abstract sculpture made of concrete since no door, window, and glazing are visible from the outside. The functional activities are all hidden in individual cells where light is provided indirectly. Circular, semi-circular and triangular punched openings in the side-walls are darkened due to lesser light, and an inconceivable atmosphere is created as if occurring in a dream. Similar conditions prevail all through the walkways, lobbies, ramps and steps. Kahn believed that an inspiring space can be created when light and silence together can produce an ambient threshold that can be realised and sensed.

The maze-like complexity and the ambiguity of space and forms are all achieved out of simple plan forms. The greatness of the National Assembly Building is indeed magical and thus unmeasurable. It has surpassed previous achievements in architecture and will probably remain unsurpassable in the future.

120th birth anniversary of Architect Louis I. Kahn

by Kazi Khaleed Ashraf

Published in The Daily Star on 1st March, 2021

February 20 was the 120th birth anniversary of the famed American architect Louis I. Kahn whose monumental architectural creation is the National Assembly (Sangsad Bhaban) of Bangladesh. Kahn’s now acknowledged masterpiece – the Sangsad Bhaban in the setting of Sher-e-Bangla Nagar – is an urban treasure in Dhaka. While the Sangsad Bhaban poses a striking architectural presence, Sher-e-Bangla Nagar displays a sophisticated complex of buildings, plazas, lakes, maidans and gardens, conceived for the enjoyment of the citizenry.

The design for Sher-e-Bangla Nagar is a climax in Kahn’s lifelong thinking about architecture, city, and humanity. Kahn was, to put it simply, one of the greatest architects of the late twentieth century. He was not only a brilliant architect but also a philosopher-poet who pondered until the end of his life about the significance of human institutions which architecture must serve. He opened up a new pathway in modern architecture. Many consider Kahn to be the initiator of post-modern architecture. Kahn’s work, as well as his compelling words, captivated a whole generation of architects – from South America to Japan, from Europe to India – into thinking about the great possibilities of architecture.

A gift to the city of Dhaka, Sher-e-Bangla Nagar is a result of the cumulative effort of a passionate architect and a group of dedicated people who navigated the project through political and bureaucratic intricacies. The construction of Sher-e-Bangla Nagar is also deeply intertwined with the making of Bangladesh. The origin of the project lies in the history of partition of the subcontinent, and the creation of an impossible nation with two separate wings and the politics of disparity that followed it. Sher-e-Bangla Nagar is largely an outcome of the growing consciousness among Bengalis to take charge of their own lives, and carve out an equitable, democratic state in militarised Pakistan. Sher-e-Bangla Nagar is the evidence of the will of a people to demand and embark on an inspirational journey for democracy and self-identity.

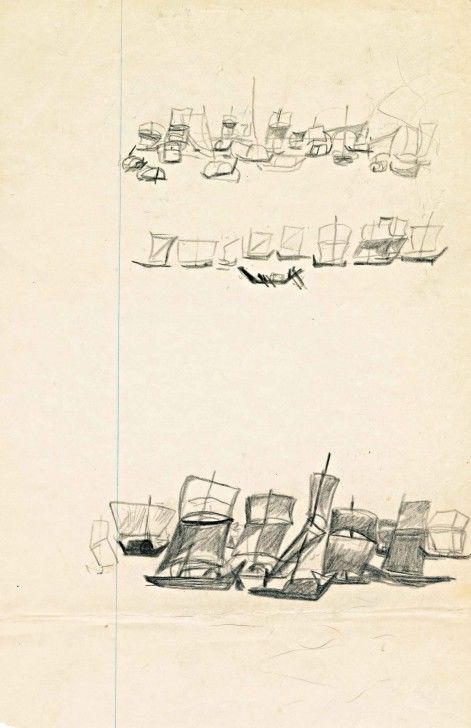

During his first trip to Dhaka, in early February 1963, Kahn was taken on a river cruise on the Buriganga. He made quick pencil sketches on the back of an envelope and some plain paper recording life on the river, especially the country boats with sails, and the riverbank. On some sketches, buildings of the riverbank indicate the Northbrook Hall and the Sat Gambuj Mosque. The riverbank sketches are being published for the first time, courtesy of Henry Wilcots and the Architectural Archives at the University of Pennsylvania (AAUP).

Louis Kahn’s Capital Complexity

by Kazi Khaleed Ashraf

Publishied in The Daily Star on 1st March, 2021

The National Capital Complex in Dhaka, designed by Louis Kahn, is an epic work in the annals of modern architecture. Even after sixty years of its conception, Kahn’s complex remains a wondrous phenomenon that is continuously renewing the purposes of architecture.

Dhaka was a critical site of Kahn’s new overtures in the modernist cosmos. Located at the geographical and ideological edge of that cosmos, the project literally expanded the horizon of modern architecture that was stagnating in its own ideological doldrums in the 1950s. In amalgamating an ancient intensity with a modern programme, and resuscitating the eroded civic purpose of architecture, Kahn was able to articulate in Dhaka a kind of spiritual modernism.

What made Kahn’s ideas compelling was the near-mystical optimism in the virtues of architecture. Through his family of forms and poetic thoughts, Kahn resorted to a re-appreciation of history and human institutions. By the time Kahn arrived in Dhaka, he had internalised history and twentieth century almost seamlessly. One could say that if he was Roman in his architectural orientation, he was Mughal too. If he was modern, he was also primordial, and if he was a twentieth century architect, he was also an ancient alchemist. Dhaka was the critical venue of that transformative moment in modern architecture.

Kahn’s preoccupations with Dhaka cannot be packaged simply within the conventional format of project developments. The significance of the Capital Complex is inextricably linked with the national and political struggle of the Bengalis. It is this correspondence between architectural form and cultural norms, often working at surreptitious levels, that has not been fully investigated.

Most critics are still unable to give a fuller assessment of the complexity of the project. While the architectural historian Vincent Scully noted Kahn’s architecture in the subcontinent as “eloquent expressions of space and structure that invoke traditional stabilities,” few have articulated how the work establishes those stabilities in innovative ways.

Organised as a miniature city, Sher-e-Bangla Nagar is characterised by two aggregations on a north-south axis separated by gardens and lakes, and ordered by a network of rectilinear and diagonal elements (of buildings, landscape components and pathways, set in both hierarchic and serial composition). In the overall plan, Kahn conceived the Assembly Building as the crown of the Complex. The southern group – the so-called Citadel of Assembly – took on a concentric pyramidal formation, with the concrete Assembly Building flanked by the attending lower brick structures (originally residences for parliamentarians and government officials).

I have argued elsewhere that Sher-e-Bangla Nagar is more than a building; it’s a landscape ensemble. And there is much to learn from that. Bangladesh’s hydrological landscape was the point of departure for Kahn’s thinking that became evident on his very first trip to Bangladesh in February 1963. He made a few sketches on a river cruise that record his impressions of the presence of water in the terrain. Kahn noted: “The two elements of nature most pervasive in the landscape of East Pakistan [Bangladesh] are water and vegetation. They almost assert their presence.” Kahn observed that in Bangladesh one needs to produce an “architecture of the land,” meaning that the fundamental building fact in that delta country is the molding of the earth to provide both platforms and proto-architectural shapes. He conceptualised that as the process of “dig and mound,” something that involves an excavation of the ground to create an earth mound on which the building is placed; the excavated pit becomes the pond.

Regarding the Assembly, many critics have sought a genetic connection of its centralised plan to Renaissance buildings such as St. Peter’s, Mughal monuments as well as Buddhist temple-monasteries in Bangladesh. With a centralised plan, Kahn was clearly trying to imbue the Assembly with a sacred and spiritual aura at a time when articulating spirituality in a modern secular world was a tricky proposition.

In his intention to tap the spiritual, Kahn was perhaps closer to the Bengali poet-philosopher Rabindranath Tagore’s claim that art is one of the windows whereby man is in touch with what he called the “eternal reality.” Kahn was known to be a member of the Tagore Society in Philadelphia in the 1950s, which makes Kahn’s access to the Bengali realm prior to his arrival in Dhaka.

The Assembly Building attains a sacred character because of the womb-like disposition of the central Assembly Hall within rings created by the ambulatory space, the seven-storey high interior “street,” and outer structures. Light of different shades and tones, constantly changing and materialising from unseen sources, animates the ambulatory space, while stairs, ramps, and walkways wrap around the womb-like chamber in a chiaroscuro.

In addition to local innovations in concrete construction for the Assembly Building, Kahn reinvigorated the poetry of brick architecture with its powerful resonance in the region. In Kahn’s new order of a brick architecture, with its geometry of form, deep shadows, earth-hugging physiognomy, and articulation of the arch with the concrete tie introduced a new vocabulary in the repertoire of regional modern architecture, and perhaps inaugurated what would be later described as “critical regionalism.”

The question whether Sher-e-Bangla Nagar is a city, and whether this spectacular symbolic machine is out of tune in the fractiousness of contemporary society, is finally redeemed by the overall landscape plan – the fabric of buildings, lakes, and gardens, and their disposition in the landscape. It is this quasi-city that is more responsive to the features of the delta than realised or discussed.

In the context of the raucous city that Dhaka has become, the environment of Sher-e-Bangla Nagar offers the image of an imaginary past – as if all Bengali cities were like this – and an imagined future, that a city could be like this. It is this fabric that I have labelled as the “Bengali city,” whether Kahn claimed it as that or not.

All three articles were originally published on The Daily Star.

Images: courtesy of Henry Wilcots and the Architectural Archives at the University of Pennsylvania (AAUP)