Abanindranath Tagore (1871-1951) was a figure who was first celebrated, then sank into oblivion, and then re-excavated. Despite his immense contribution to the history of South Asian culture, Abanindranath was often dismissed as a mere illustrator of fairy tales. In reality, Abanindranath Tagore in inaugurating the Bengal School of Art movement was the first prominent figure of Swadeshi values in Indian art. It was this movement that eventually led to the rise of modern Indian paintings[1].

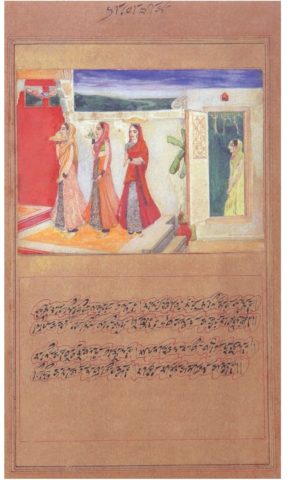

Krishna Lila – Bhabollasa, Image courtesy: Rabindra Bharati Society, Kolkata

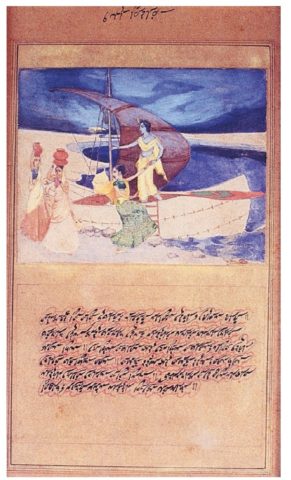

Krishna Lila – Nau Bihar, Image courtesy: Rabindra Bharati Society, Kolkata

Abanindranath’s mastery was in miniature paintings. In small scales, he was able to capture stories from diverse cultures which spanned hundreds of years. Within a canvas of five inches by eight inches, he could make one travel from 8th century Baghdad to the Kolkata of 20th century. “His telescopic vision looks far into history, gathers that world in, and projects them again into the present,” says Sonia Amin, historian and professor who is researching on Abanindranath Tagore and his miniature painting. “And the result is a temporal palimpsest of past and present.”

In his little miniatures, Abanindranath deals with the largeness of scale, which is evident in his work Shahjadpur Landscape. “He also weaves the past and present into one seamless entity,” says Sonia Amin. The reason Abanindranath was called an illustrator is because he took part in oral traditions. He made portraits and masks, but apart from that, being the multifaceted figure that he was, he also did a great deal of writing. Specifically, he took interest in folk tales. We know these folk tales are oral traditions translated into written forms. Sonia Amin believes Abanindranath translated them again into paintings, and he did so “without losing the elusive, diffuse, nebulous large character of the tradition in the first place.”

Shahjadpur Landscape, Image courtesy: Rabindra Bharati Society

Abanindranath on the South Verandah, 1944, Image courtesy: Rabindra Bharati Society

Sonia Amin also argues that to understand Abanindranath’s explorations, one has to understand the Jorasanko culture and ambience, and the effect that had on him. Perhaps one of the biggest turning points of his artistic career arrived when he leafed through an old, illuminated Indo-Persian manuscript at the ancestral library in Jorasanko[2]. It was in that manuscript that he came across fantastical drawings and calligraphy which charged up his imagination and inspired him to explore this new artwork. He would eventually refer to himself as a ‘Mughal miniaturist’.’

Abanindranath began working on famous series of paintings soon after that described the well-known scenes from the life of Sri Krishna. Experimenting with Rajput and Mughal art styles, he made a number of paintings based on the lives of Radha and Krishna. This series is popularly known as Krishna-Leela and considered to be from the earlier phases of his painting career, from 1901 to 1903.

Japanese influences also existed in Abanindranath’s artworks. He studied Japanese art under the artist Okakura Kakuzō, when the latter visited India from 1901 to 1902[3]. In his later work, he began to incorporate elements of Chinese and Japanese calligraphy traditions into his art, seeking to construct a model for a modern Pan-Asian artistic tradition that would merge the common aspects of Eastern spiritual and artistic culture.

Abanindranath next worked with Islamic themes, especially focusing on tales from the Arabian Nights. During this period, his notable works included paintings of Sheherzad and King Shahriyar, as well as those of Mughal Emperor Shahjahan. In an article called The Arabian Nights and the Web of Stories, the Indian art historian, R. Siva Kumar writes: “The Arabian Nights was not merely a text he chose to illustrate but was in itself a palimpsest of memories culled from many cultures and churned into a labyrinth of stories which he used to add depth and resonance to his readings of the present. We could call it a collage or a narrative conjoining of different times and spaces.”[4]

Abanindranath’s work is a reflection of erudition and multiculturality, with influences of Bengali, Arabian, Persian and Japanese culture, sometimes even an amalgamation of these cultures. In his vision and perception, Abanindranath Tagore was a modernist and way ahead of his time, which he proved through his diverse collection of work. Perhaps the biggest impact Abanindranath’s work was in shattering the preconceived notions held about Bengal’s art, and pointing out that it does not follow a linear history.

References:

This article is from the Vas Issue-4