I Promise

by Khwāja Shams-ud-Dīn Muḥammad Ḥāfeẓ-e Shīrāzī

Has not the Architect, Love, built your heart

in a glorious manner,

with so much care that it is meant to break

if love ever ceases to know all that happens

is perfect?

And where does anything love has ever known

go, when your eye and hand can no longer

be warmed by its body?

So vast a room your soul, every universe can

fit into it.

Anything you once called beautiful, anything

that ever

gave you comfort waits to unite with your

arms again. I promise.

[Hafez’s poem introduced here upon the request of Firdous Azim]

Bashirul Haq was one of the few Bangladeshi architects whose works considerably influenced the shaping of contemporary architecture in the country. In a career spanning over 45 years, Bashirul Haq designed over 250 buildings while also contributing as a planner and an educator. Suffering from various health issues, he passed away on 4th April, 2020.

Bashirul Haq completed his Bachelor of Architecture from the National College of Arts, in Lahore, Pakistan in 1964. Upon return to Dhaka after graduation, he worked in the office of Muzharul Islam. In 1975, he received a master’s degree in architecture from the University of New Mexico. During his time in the USA, Bashirul Haq met the famed structural engineer Fazlur Rahman Khan. Khan advised Haq to join the Chicago-based firm Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM), but Haq decided to return to Bangladesh.

In 1977, he established his own architectural practice, Bashirul Haq and Associates. During that period, he won the national design competition for the Bangladesh Chemical Industries Corporation (BCIC) headquarters in Dhaka. However, it is the remarkable body of residential designs that made him stand out from his contemporaries. His design of homes and housings such as Dhanshiri Apartment Complex, Bhatshala House in his village in Brahmanbaria and Kalindi Apartment Complex are great examples of subdued and modest masonry volumes. The architect’s own residence and studio in particular express his sensitivity for the domestic realm. With the use of natural light, greenery and tactility of the building materials, he enhanced the experience of being at home.

In 1989, he returned to the United States after a long break as an invited design critic at Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Following the devastating cyclone in Bangladesh in 1991, Bashirul Haq and Associates was commissioned by an NGO named PRISM to design three community development centres and cyclone shelters in the Cox’s Bazar district. The project was shortlisted for the Aga Khan Award for Architecture in 1994. Haq’s other two notable projects, his own residence and studio and the Bhatshala House were also shortlisted for the award in 1980 and 1992, respectively. In 2004, Haq was commissioned to design the new campus for the school of music and dance at Chhayanaut in Dhanmondi. He also designed other institutional buildings in Dhaka, like the campus for Sunbeams School in 2007 and East West University in 2012.

Bashirul Haq was a member of Master Faculty at Bengal Institute for Architecture, Landscapes and Settlements and remained involved in all its major events and activities. In 2015, he conducted a month-long session titled “Home and Dwelling,” at Bengal Institute, consisting of a design studio and lectures. In 2016, he participated in a panel discussion titled “Architecture that Validates” at Bengal Architecture Symposium NOW/NEXT, organised by Bengal Institute. His projects were exhibited as part of the travelling exhibition “Bengal Stream: The Vibrant Architecture Scene of Bangladesh” in Basel, Switzerland in 2017, and later on in Bordeaux, France in 2018 and in Frankfurt, Germany in 2019. He also presented at the Swiss Architecture Museum in Basel in 2017 as part of the travelling exhibition.

In 2018, Bashirul Haq was honoured with the Hamidur Rahman Memorial Award for his contribution to the field of architecture. A monograph of his works and philosophy titled Bashirul Haq: Architect, edited by Iftekhar Ahmed and Sheikh Rubaiya Sultana, was published in 2019 by Copal Publishing with the Department of Architecture of BRAC University.

[Written by: Farhat Afzal]

Home and Studio, Indira Road, Dhaka, 1981

In these times of self-engrossed existence, we often wallow in the guilt of not having expressed our gratitude to the living. I was very fortunate to have had the opportunity to convey my deep gratitude to Bashir Bhai.

These words in Bengali, were conveyed to him on his winning of the Hamidur Rahman Puroshkar 2018:I express my gratitude to Bashir Bhai, not only at a personal level but on behalf of all architects involved in the profession of architecture, in Bangladesh. All of us have been directly and indirectly benefited from his art.

We, the architects of Bangladesh consider ourselves very fortunate.It is only in 1967, after a hiatus of two hundred and thirty years, that our first home-grown architects left their academic spheres, only to come into the birth pangs of a war torn new nation followed by re-building, the effects of which lasted a decade.

The fact that, in a period of just over thirty-five years, our architecture has been able to eke out a place for itself, is remarkable. Particularly so, since having almost started at zero, its practitioners, after unlearning, had had to contemplate, assimilate, internalise and find adequate expression to their art to be able to catch the attention of their international peers.

Even being a partisan commentator, I feel, it is difficult to overestimate this success.How did this success come about in such a relatively short time? Fortunate are we that the very outset of this new journey was made by some very sensitive people like Bashir Bhai. Not only competent, I would like to stress on the word “sensitive people”.

Equipped and properly trained abroad, Muzharul Islam was the first to return home in 1952 to lay the firm foundations of the right kind of architecture here on his own soil. He was instrumental in getting Louis I Kahn here. His architectural masterpiece stands like a beacon in our midst holding up high, the humbling, quality-defining bar.Starting alongside the new young architects, Bashirul Haq came back home from the US in 1977 and was met with exciting new commissions.Despite having a strong international exposure, both Muzharul Islam and Bashirul Haque were very firmly rooted in Bangladesh. They were sensitive, and very compassionate as human beings, standing firm on their rooted grounds at the same time aware of the current architectural dialogues. What more could a new nation starting out wish for? What were the odds of getting not one, but two such people to pave the way?

The starting generation of architects were, thus, presented with a windfall of a sensitive architecture rooted in the local yet in conversation with the global, a state which is reached through a long winding process fraught with wrong turns and mistakes which needs to be painstakingly undone.These solid and sturdy foundations allowed the successive generations the luxury to get past the dust-storm of globalisation and move forward with their eyes wide open to express themselves.

A lot has been said about Bashir Bhai’s architecture. A monograph of his work has also been published replete with discussion on his style.Some repetitions are healthy, I feel.

Even a novice can tell that his is an architecture which stands boldly with the complete inherent tactility of one single material, the brick, forged from the soil of the Bengal delta.

His architectural expression crosses borders, with the naturally heavy presence of the brick wall. His treatment of the bricks in a wall, brings to my mind the famous Kahn conversation with the brick. Bashir Bhai’s brick walls seem to similarly reply, “I like small openings. I want to be less dependent.”The brick walls in this delta are handmade all the way. To the discerning viewer, the touch of the hand is visible on the brick and can be just as visible in the crafting of the wall. The brick in this delta carries with it the stories of a thousand years.

Craft as a passion has been ingrained into the ‘student’ in Bashir Bhai, through all the three stages of his life. He spent his childhood years growing up in the villages of our delta, then moved to the heritage city of Lahore in his youth where he was being introduced to the first formal design education, and finally polished up in the settings of the simple and beautiful elegance of the traditionally hand-crafted buildings of New Mexico.

It is of little wonder that his sensitive demeanour allowed his architecture to be so effortlessly driven home once he was back practising in a setting he felt very much at home in.

The most remarkable of his traits, I can identify, is how untouched he has returned from the exuberance of a comfortable socio-economic exposure he has had in the west. He never for a moment lost sight of the need for thrift, within the realm of his much poorer fellow citizens. His architecture is, therefore, achieved with a minimal cost, clearly devoid of anything superfluous.

The depth and internal consistency of his inner convictions can be seen, without much doubt, in both of the houses he built for his own family. Since bathrooms are the most expensive part of a house, he spent his life with a single bathroom for three bedrooms and only one shared by both floors of his village home in Bhatshala.

The fact that nature and environment are inseparable from the human habitat has always been a given, in all his residential architecture, even while building for developers, in this city with very expensive urban land.

The volume of the built-up spaces have always been optimised at a level to ensure that spaces for nature are balanced in all his residential projects.

We are forced to bid a physical goodbye to this great man. However, architects in Bangladesh, will not forget that we stand with a certainty and sureness on the sturdy foundations that one of our first architects, Bashirul Haq has hugely contributed to.

Asra Apartments, Dhanmondi, Dhaka, 2003

Bashir (Bokul) was in the third year when I joined the National College of Arts. There was an outstanding student in every year, Bokul was in his. A thinker, fond of reading and a brilliant designer, he was not only popular amongst us, his fellow students and professors, but also liked by the peons and small shopkeepers near the NCA hostel. When he left for then East Pakistan in 1964, he was missed by all. He had left wonderful memories for all of us.I think it was in 1983 when I had the fortune to meet him again in Dhaka. I was hired by the general manager of Grindlays Bank to refurbish their headquarters. On my arrival, I was told by the GM that I was to have a local partner. He had already invited an interior designer to work with me. Knowing Bokul’s architectural sensibility, I knew he would be a renowned architect of the country. I told the GM I want to work with Bashir. Luckily a young banker knew him, and called his Bokul Bhai, who arrived soon. When we met, it did seem that we were meeting after almost twenty years. We picked my luggage from the five-star hotel and went to his house. A feat of brick house, deeply modern yet deeply rooted in Bangladeshi culture, both tangible and intangible, it was my first introduction to his work. I met little Partho, who became a great friend.

Bokul showed me several houses, the Ispahani’s Apartment Complex and a building located in Dhanmondi. He had developed a unique architectural language embedded in local architecture idiom. The use and details of brick masonry work was fascinating. There are many things about Bashir I did not include, however one thing is the importance he gave to details. While I was staying at their house, he was designing a staircase for some building. He worked on it for three days himself. This care for details was important for him.

I had a better understanding of his architecture when by default I attended the Aga Khan Award for Architecture Conference held in Dhaka in 1984. At the conference, Bashir talked of looking critically at the traditional/ historical buildings, the Bangladeshi culture and the natural environment. For me, the lecture was a lesson about architecture.

His death shocked all his Pakistani friends. We are deeply grieved, and we will cherish his wonderful memories. Our thoughts are with Firdous and both the boys. May they have the strength to bear their loss.

Drawing of Multipurpose Cyclone Shelter for DASCOH

If I have been able to become an architect it is by standing on the shoulders of a few giants, Bashirul Haq is one of them. I saw Bashir bhai for the last time at a family dinner on 31st January 2020. It was the night before the mayoral election in Dhaka, at a small gathering of family and friends at Dr. Syed Anwarul Hafiz’s residence watching his biopic. Bashir bhai was in a bright orange panjabi wearing his ever smiling face and that’s how I would like to freeze him in my memory.

Bashirul Haq was a world-class architect and a good human being, a rare breed and hard to find. His wisdom, generosity and humility will remain as inspirations, and the values he upheld as a professional is a benchmark for us to follow. But most importantly his light-hearted wit will always bring a smile to the faces who met him once.Bashirul Haq is and will forever be regarded as one of the few who held high the architecture culture of Bangladesh. His contribution to education and practice will remain a strong legacy to be revered by generations to come. We are desolated by his departure. He will be missed immensely.

Asra Apartments, Dhanmondi, Dhaka, 2003

Bashir Bhai loved brick. This is more than a constructional fact. Although he has built in other materials, there is something about brick and Bashir Bhai that exude simplicity, elegance, and reasonableness. I have always thought if Bashirul Haq were to ask brick what it wanted to be, brick would have replied: simply stacked and laid, and not make too much fuss. Perhaps with a scintilla of poetic mystery. Most of Bashirul Haq’s architecture is a quiet, unpretentious assemblage of bricks that are simply and methodically stacked. With a scintilla of poetic mystery. The period when Bashirul Haq began his practice required that kind of clear quietude and determined decorum.Bashirul Haq straddles a particular moment in the architectural trajectory of Bangladesh, a period of hiatus in the 1980s, when the production of Muzharul Islam has slowed down, the band of foreign architects have left town, and a directionless, commercialized culture has taken over. His work in those times demonstrated a quiet resolve to produce simply a decent and reasonable architecture, and in a silent and persistent way arrive at something Bengali. His works defined residential architecture in Dhaka in the 1980s onwards and the unique apartment complexes described the only successful group housing in the country.

By reasonable I mean something derived from a logic of purpose, materiality and livability, but attuned to human content, something that eludes many architects today. Rejecting virtuosity, or what Muzharul Islam would call “flourish,” Bashirul Haq’s work will remain exemplary for a long time and puzzle those who produce unexplainable and irritable gymnastics in their work on why his buildings receive such admiration. Bashir Bhai knew the unutterable secret art of the architect – the kind of work that brings you home.

Being Bengali in a contemporaneous and conflictual society is not easy, and doing Bengali architecture is far more difficult. Bashir Bhai did not do any of that in an announced way, but whenever one entered a building by him one simply felt the mysterious resonance of a Bengali homeness. Perhaps it was the brick lay, or how brick secretly resonated with human tactility, or how the building hummed in the landscape, or how the openings were modulated in a rhythm, or how the layout seemed deceptively easy, or how all that came together as a decent demeanor. If buildings had character, which European architects in the 19th century pursued in a methodical way, Bashir Bhai’s buildings would be described as “bhodro.”

Like his work, Bashir Bhai himself conveyed gentleness and generosity, yet with an assuredness that was easy and not brash. In the photograph of Bashir Bhai visiting his village home in Bhatshala along with Bengal Institute participants, he sits relaxed and pleased – literally at home – leaning against a column, almost at the precipice of architecture, ready to receive as well as offer visitors gems gathered from a life of that miraculous profession that is architecture.

Never clamoring for recognition, and often unsung for his role, Bashirul Haq will be remembered as one of the few masters in Bangladesh’s architectural cosmos. With the ongoing COVID-19 crisis a defining condition in our time, when the whole globe is certainly taking on a new turn, the passing away of Bashirul Haq is a poignant signal of the end of an epoch in more than one way.

AK Khan Ain Bhaban, Chittagong University

I have known Bashirul Haq (Bashir Bhai) from 1969 when he was working as an architect. He was a family friend and helped my father in designing our house in the early 1970s. I was again in regular contact with him in the 1980s. Both he and his kind wife Firdous Azim were widely known in Dhaka as one of the most gracious and affectionate couples. I again met him for the last time in Singapore around 2010.

As an elder brother and friend, I remember him as a warm, considerate, kind, generous and helpful person. His optimism and charisma inspired everyone who knew him. May Almighty Allah grant him paradise.

Bhatshala House, Brahmanbaria, 1989

A letter to a departed soul

Dear Bashir Bhai,

What is it I can say or write about your absence without talking about your presence in me. It’s been only a few days that you have taken a path of no return and in which we will all take part without a doubt. Now that I am here, waiting for my turn to cross that threshold, I ponder with love and respect on the days we met and greeted each other. I remember our very first meeting. Do you recall that day or where? Let me remind you. It was way back in 2001, I came back to Dhaka after a long stay away from here. Dear friend Pablo, Ziauddin Khan, took me to your studio, where I met you for the very first time, and of course was spellbound to feel the strength you possessed as an architect in Bangladesh, and for Bangladesh. I was a fresh graduate then, and had just received my Master of Architecture degree from the University of Pennsylvania only a few years back. So, my capacity to understand you was from where I stood as an architect then but your gesture and curiosity to know me, was filled with such grace that, I felt, I was the tallest architect in town. You embraced me whole-heartedly, and made itme feel so right to leap across the ocean to return to Bangladesh. That very hand shake of yours, shook the ground beneath me, only to find the right layer to plant my seed of commitment as an architect for a place and by a place. Since then, we have met many times, and shared precious ideas to be good in what we do as humans. Now I can proudly tell you, that human understanding in me has made me a better person, and definitely a better architect. We often talked about things that are more on the essence of architecture than buildings. Your immense interest in transcendental matters, and how you put your energy to understand our place on earth has played such an important role in your work that it will take years for us to fully grasp. I know that I probably would have been a different person, and of course a poorer architect in thinking, if I were not have had the opportunity to meet you, and known you in person. I cannot thank you enough for pulling me next to you in many of the student work reviews. How you ushered generations of young minds to feel and understand the strength of architectural thinking, which can only be felt through their own personal journey as architects. I am absolutely sure of your offering in thinking better has and will carry them far and beyond.

Bashir Bhai, how can I tell you enough that you will be missed in my life? Like many, I am also holding myself in the guilt box and blaming myself that I did not see you often enough. I wish I had done that to understand you and your thought process better. I know this will haunt me for years to come but please do accept my apology. None were done intentionally. If that were the case, I would not be sitting here and trying to let you know that you are deeply missed.

Remember the great walk and talk we had in Basel, Switzerland. We walked almost all day and saw, discussed and rejoiced the essence of what we found meaningful works of architecture. Later in the evening, sitting in the hotel lobby, sipping our hot wine in the middle of chilling December. That was fun and moments to be cherished. Having the age differences between us, you never made me feel that I was too young to be a part of your evening hangout. On the contrary, it was totally the opposite. I felt like we have been friends for ages, and we could discuss almost anything, and we did. So, thank you for giving me that space in you.

The other day, I was going through my drawing folders to share a drawing of yours with some of the participants in my studio. It was a detailed sectional drawing of your Dhanmondi, Road 4 apartment project. I was invited by Safia Azim Chukku to help her apartment interior work in that building. Knowingly, I was entering into the realm of Bashirul Haq, I was nervous and cautious at the same time. I did not want to walk into your world to crack open a window that brought north light through the south window. Immediately after being commissioned, I went to your studio to understand the building and your intentions behind the project. How open-handedly you ushered me into your architectural world. Like many projects of similar merit, Dhanmondi Road 4 project was also an inch closer to your own understanding of tropical architecture. We sat around your drawings for hours. You shared your drawing set with all intricate details, and in the end, you gave me a drawing without having any doubts whether I was the right person or not to share that beautifully executed drawing of the window detail. I also remember your quiet attention and gaze on my published sketchbook on Japan. I was so happy and lucky to have shared my understanding of Japan with a mentor like you. Do you have any idea how far those moments of yours looking through my book have pushed me? Well for your information, they pushed me to see a few other personal works into the printing house. I wish you were with us to see these upcoming publications. My hats off to you Bashir Bhai for making me believe in my own ability and giving me the courage to share my own works with the minds, which are young and bright.

Bashir Bhai, I feel sad for not being able to attend your funeral. The situation was as such, that I could not come out to whisper my last wish to your ears. Now that you are gone, I feel a sense of emptiness in me. I know you are always here in your spirit and I can find you at any time in any of your buildings. So, with that comfort, I will move forward and hope that, someday, somewhere we will meet again. Alright then Boro Bhai, rest in peace and never think that you are not loved by all those you have left behind.

I love you and miss you dearly.

Yours,

Salauddin.

Dhanshiri Apartment Complex, Indira Road, Dhaka

Timelessness: A tribute to Architect Bashirul Haq

Only few architects are capable of harmoniously combining the general and the specific. Bashirul Haq’s work embodies this synthesis in an exemplary manner. In his architecture, the universal and the local go hand in hand as much as pragmatics and poetry, tradition and modernity.

Bashirul Haq’s buildings are based on timeless, primordial architectural means such as space and geometry, which lend them a general comprehensibility, and a charisma that touches people of all origins or ages. On the other hand, their materiality and elaborate construction are subtly adapted to the specific local context, its climate and geography. In this duality that oscillates between spirituality and pragmatics, Haq’s built ideas become humanistic tools that serve society in manifold ways. They reflect the collective feeling of a community as well as the individual, everyday needs of each and every user. In a vital dialogue with the changing fluid landscape, and the rapidly transforming society of the Ganges Delta, they exude grounding and confidence. They give me a feeling of welcome and tranquillity, while at the same time engaging me in a lively, challenging dialogue.

With Bashirul Haq, the architectural community has lost a true master of his craft, a superior designer, and a critical and alert spirit that has always operated at the height of its time without being distracted by superficial and fashionable trends. May it be a ray of hope that his timeless work will inspire many generations to come.

Nijera Kori Training Centre

A Tribute to Bashirul Haq, Architect

I had my first opportunity to meet Bashir in Dhaka in the early 1990s. I had heard a great deal about him and his work that made me excited to meet him. Despite our first meeting being the result of myself and mutual friends rudely and embarrassingly waking both Bashir and Firdous at 1:30 am in the morning, we were welcomed by them with warmth and graciousness. I was so embarrassed that I cannot remember what we talked about, and did not go to see him again for about a year.

When we did meet again, Bashir became a fast friend and mentor despite our differences in age and background. For thirty years after that, I would begin every trip to Dhaka with a visit to see Bashir, and by making plans to visit his current projects or a project I hadn’t yet seen. The visits would start at his house at Indira Road, both of which to me were indicative and beautiful representations of his architecture. The house demonstrates how Bengali craft, materials, construction and art can articulate a modern Bengali architecture that is as rich and sensual as its historic and rural forms, and one that feels like home. The architecture of the house resonates with the stories Bashir told about his childhood spent in villages, as well as the urban worldliness that one would encounter in him.

During our visits to see his projects, it always surprised me that Bashir, with all his talent and knowledge, could be interested in the observations of a much younger and less experienced architect like myself. For me, his projects demonstrate how design can be rigorous, intellectual and creative at the same time. Bashir’s work taught me that architecture must give back more than is asked of it, in order to shift the status quo and to help transform the world we live in. Transformation seemed to be what Bashir’s work was often about. His country house in Bhatshala transformed one’s experience of the rural landscape; the early residential apartment project in Moghbazar invented an urban form that suggested the possibility of a transformed Dhaka, and his apartment building in Kalindi created an elegant prototype for the city in its embrace of multi-family residences. A complete list of Bashir’s innovations would be long!

Bashir was insightful to the point of being uncanny. He would understand people and situations quickly, get to the heart of a matter in any situation, and befriend anyone. It is no wonder that he had countless devoted friends and connections.

A young client of mine in New York City once asked me about Bangladesh, and told me that she was interning for a film production that was to be partly based in Bangladesh. Months later, I received a call from the filmmakers explaining that they needed to go to Dhaka to film the Shangshad Bhaban, and asked if I could help organise it. The project seemed real and serious enough but they needed the filming in Dhaka to happen soon, in an absurdly short amount of time. I was about to give up on the idea of helping the project when it occurred to me that Bashir could make this happen. After a call or two, Bashir decided to help, and sure enough he figured out how to cut all the red tape. The travel and access problems were solved, and the filmmakers ended up shooting more of the film in Dhaka than anywhere else in the making of “My Architect,” and in the process, became good friends with Bashir.

The qualities of kindness, empathy and generosity that allowed Bashir to help an unknown film crew are also the qualities that made him a friend, mentor and teacher to me. He lived a very rich life that was full of achievements, and he shared his talents selflessly. Bashir never failed to inspire me with his enthusiasm, intelligence, creativity and love of life, and for this I will always be grateful.

Dhanshiri Apartment Complex hand drawn drawings

The Dawning of a Friend

Speaking of the famous cartoon that looks alternatively like a duck or a rabbit, Wittgenstein asked when does it look like one or the other, and what does it tell us about how we see. Stanley Cavell understood this seeing more inter-subjectively asking when does one aspect of someone rather than other aspects dawn on our awareness. To this conversation, Veena Das adds her voice to say that it takes a life with others for different aspects of them to dawn upon you. Such then is the context in which I reflect on my life with Bashir, and how his being a friend dawned on me.

The earliest memories I have of Bashir are of him as already a well-respected architect, on his way to becoming famous for his singular ecological style, and a friend of my family. Bashir Uncle, as I first knew him, would drop in at our place with Firdous Azim back in the days when such modes of sociality were the norm, and they would guffaw with my parents while drinking tea and eating samosas and snacks. Reminiscing about him over the phone the other day, my mother recalled some of her favourite jokes he had cracked with her and chuckled, even now feeling the pull of his charismatic personality.

Even though I adored their visits, Bashir was still a distant figure, an adult in a world of adults from which I was still in exile. The amazing thing was the rapidity with which I was included in the world crafted by Bashir and Firdous, as they came to be known to me as I progressed in life. In a society in which younger generations are often subtly overlooked or undermined, Bashir and Firdous enjoyed younger people and took pleasure in being in conversation with them. Pretty soon, Bashir and Firdous were coming to our house to pick me up to take me out for dinner to hear more about my fieldwork in the chars, and to tell me of their travels, what they were reading, who they had heard speak, what their sons and their friends were doing, etc. Their tree-shaded house, tucked at a recess from the busy hub of Farmgate, felt like a sanctuary for adda, instead of the small talk that flourishes in such large quantities in many social gatherings.

I had an idea to visit all of Bashir’s most favorite buildings with him and Timmy Aziz, an architect and friend to both of us, to write a photo-essay on Bashir’s notion of dwelling, taking dwelling in the Heideggerian sense of a bringing together of sky, earth, mortals and divine beings or the eternal. While our schedules didn’t allow it at the time, any time I felt the doldrums or wanted to think of a horizon beyond my present I would recall the idea. It would fill me with joy to imagine ourselves walking around with Bashir, chatting with him about the environments he sought to craft with his choice of materials, use of light and imagination of those who would live in them, and future generations who would traverse them.

A few years ago when I went back to Bangladesh over summer break, I was really saddened to see Bashir very weakened after a recent bout of Chikungunya, and all the complications that came with it for him. He seemed very frail, holding himself gingerly, and being cautious in his movements. As usual, we were meeting over a delicious meal at their house with many others present. By this time I had met and befriended their eldest son, Tariq Omar Ali, Rene to most, who is a historian, and was visiting with his parents. There was much talk and laughter. Initially, I was a bit reticent around Bashir, painfully conscious of the physical changes in him, and not wanting to tire him out. I can’t recall the specifics of our exchange but all of a sudden I found myself laughing out loud at something Bashir said, with all else forgotten. I have a mental shot of his face with its broad smile, caring and curious, eliciting all kinds of confessions from me about my family and my work, as though it meant the world to him to hear it all. Bashir Uncle, Bashir, Bashir my friend.

Chhayanaut Sanskriti Bhaban, Dhanmondi, Dhaka, 2005

The Poet of Brick

Bashirul Haq was a poet who crafted his poems with the language of brick, while green, light, air, and tactility serving as its syntax. Some of his brick buildings are like inhabitable poetry, where one experiences space as one would read, say, Jibananando. Louis Kahn once famously asked “What do you want, brick? And brick says to you, I like an arch.” If this was Kahn’s celebration of the brick’s quintessential material property (that brick can only be an arch but not a lintel), Bashirul Haq expanded that property into the realm of poetics, meditating with bricks, and bringing them home, where they naturally belonged: the Bengal delta.

Bashirul Haq’s design epitomized an entwined brand of indigenous and modernist impulses in Bangladeshi architecture since independence. For the new nation of Bangladesh, the decade of the 1970s was a complex tapestry of optimism and pessimism. Amidst the social tension of the decade, a new generation of ambitious architects burst forth onto the architectural scene of Bangladesh. The outcomes of a few national architectural competitions revealed new visions of modernity, building technology, and architectural space. Institutional and commercial buildings were no longer bland boxes, comprising corridors and rooms. In 1977, Bashirul Haq won the national design competition for the Bangladesh Chemical Industries Corporation (BCIC) headquarters in downtown Dhaka’s Dilkusha Commercial Area. His entry showcased a new type of design energy that synthesized modernist aesthetics with a reasoned consideration for the local climate, a low budget and a dense urban context.

Many of his subsequent brick buildings are considered architectural icons of the country, suggesting a sublime modern abstraction of Bengal’s geographic ambiance. Haq’s work is of utmost importance to explain how the notion of ‘critical regionalism’ informed architectural modernism in Bangladesh since the early 1980s.

Born in 1942 in a village named Bhatshala, Brahmanbaria, a district in east-central Bangladesh, and about 100 km from the capital Dhaka, Bashirul Haq developed a particular fondness for Bengal’s rural landscape. He received his Bachelor’s degree in architecture from the National College of Arts in Lahore, West Pakistan, in 1964. Lahore introduced him to the monumental architecture and gardens of the Mughals. Before he left for the United States in 1971 to pursue higher education in architecture, Haq worked in the office of Muzharul Islam, the first Bengali professional architect in East Pakistan.

Haq’s journey to the United States played a formative role in his career development. He received his Master’s degree in architecture from the University of New Mexico in 1975. The south-western American state of New Mexico sensitized him to the transformative influence of landscape on aesthetic development. In this state, the famed American artist Georgia O’Keeffe was deeply inspired by the phenomenology of layered limestone cliffs, rugged mountains, rock formations and the meditative dance of light across them. Haq, too, experienced firsthand in Albuquerque, Santa Fe and beyond the introspective power of a place, and how its paradigmatic adobe architecture could embody the spirit of a unique terrain.

Bashirul Haq was fortunate to find a mentor in Fazlur Rahman Khan (popularly known as F.R. Khan), a fellow countryman, partner of the famed Chicago-based architectural/engineering firm Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM), and structural designer of Chicago’s Sears Tower (now Willis Tower), the tallest building in the world from 1973 to 1997. The SOM stalwart took Haq under his wing, and encouraged him to join his Chicago firm as an architect. However, as fate would have it, Bashirul Haq, already in his mid-30s, chose to return home to Bangladesh. He was ready to embark on an architectural journey in the land he knew best.

Bashirul Haq creates a cosmopolitan architecture, one in which the very premise of the local/modernity dichotomy is robustly resisted. Rather, he seeks to conflate an architectural archetype with a perceptive understanding of temporality and the spatial sensibilities of Bengal, but ultimately transcending the exigencies of the local. Experiencing his architecture, particularly his red-brick buildings, reminds one that searching for local inspiration does not have to be an inflexible moral burden, in the same way one feels that Alvar Aalto’s Säynätsalo Town Hall (1949) seems to remain embedded in some kind of Finnish genius loci, while ultimately suspending the very need to be Finnish as an expression of aesthetic authenticity. In many ways, the exquisitely delicate use of brick in Haq’s work, for example the architect’s own residence on Indira Road in Dhaka, performs Bengali folk dance and western ballet at the same time.

To understand how Bashirul Haq resisted the temptation of compartmentalized historiographies of local and global (or East and West) one needs to appreciate the ways he values his cross-cultural architectural education. Like Muzharul Islam, Haq grasped the power of diverse geographies, and how their cultures could blend together to produce all kinds of aesthetic chemical reactions. It is in this space of multivalence that Bashirul Haq’s architecture achieves a timeless aesthetic appeal that eschews the moral burden of having to be local or modern or both.

Dhanshiri Apartment Complex, Indira Road, Dhaka

Bashir: Far Away, Close Friend

I met Bashir in 1984 when the Aga Khan Award for Architecture decided to organise its first Regional Seminar in Dhaka. The theme of the meeting was decided with a group of Bangladeshi architects. I did not have one representative organization but had a tripartite group of architects, in order to bring the profession together. These three groups did not see ‘eye-to-eye’ at that time. However with the leadership of Muzharul Islam and an international opportunity of exploration, they came together with good will, and a love and dedication for architecture. At the end of a few series of serious discussions, we agreed to select the theme ‘Regionalism in Architecture’. That was exactly the theme I wanted as well.

Our collaborators in Dhaka were a very intellectually sophisticated group of young architects who were mainly inspired by the masterly Bengali architectural figure Muzharul Islam. The demands of organising for international participation were difficult to entertain but not impossible. They wanted to have Paul Rudolph, Kenneth Frampton, William Curtis, and other leading figures of architecture, namely Charles Correa and Geoffrey Bawa, in order to take part in the event. Fortunately, the event was realized, and accomplished exactly as they wished.

Bashir was in that group of organisation. He was young at 44 years of age, and architecturally mature to have developed his own idiom that did not get compromised with modernism, and one that was extremely relevant to South Asia. His approach would conform with the title of the seminar, and had the theoretical undertones of Kenneth Frampton.

During my many visits to Bangladesh, Bashir and his very sympathetic and hospitable wife Firdous Azim invited us many times to their ‘Bashir-designed’ house. Their house from decades ago was completely green. Not in the sense of the endemic green movement of the last decades. But it has been there as a natural part of the design. Even though the soft lush green creepers totally covered his elegant brickwork, they were happy to have the house and architecture of Bashir to be engulfed by nature.

Bashir used local brick structurally for his low rise building, and used the same for mid-rise dwellings. He used canopies, cantilevers, passages, bridges, underpasses and verandas as the essential parts for the climatic comfort. These features affirmed Bashir’s talent and commitment to indigenous brickwork, and culminated in a novel architecture for Bangladesh.

The Iong pleasant discussions with Bashir gave me the impression of a mature talent who takes his work seriously but not his own self. For me, he was an exemplary modest person. In every discussion, however serious the subject may be, he never spared a deep thoughtful smile suited to him as an emblem of his warm personality.

Although we have always been away from each other, two continents apart, I always felt very close to him. I have always appreciated his warm personality and good humour.

I shall miss him, as a lifelong friend, with his meaningful and sincere smile for good.

Bashirul Haq at his studio

I was probably in my second year at BUET, when I first visited the office of Bashirul Haq and Associates at a two-storied building in Dhanmondi Road 13, which is now the RANGS Anam Plaza at the corner of Road 6A and Satmasjid Road. After graduating from BUET in 1983, my classmates Neelu, Asad and Sheema joined Bashirul Haq and Associates, which by then moved to his brand new office-cum-residence at Indira Road. It was a wonderfully crafted brick building that became a place of pilgrimage for young graduates. I used to go to his office to study the wonderfully hand drawn working drawings. Among many architects, who later became successful like A J M Alomgir, Uttam Kumar Saha, and Rashedul Hasan, worked in his office.

I have many fond memories of spending time with Bashirul Haq. In 1987, I went to Lahore with him to attend an architectural workshop held at his alma mater National College of Arts (originally Mayo College of Arts), which is one of the two earliest art colleges in the subcontinent. At that time, I was very young and was privileged to accompany him to dinners at the houses of his two close friends and classmates, architect Yasmin Cheema and the Aga Khan Award Winning architect Nayyar Ali Dada.

Besides architecture, Bashirul Haq was involved in planning, research and teaching. In 1999, German Red Cross published a book “Battling the Storm-Study of Cyclone Resistant Housing” on house-forms of the coastal regions of Bangladesh, which was co-authored by him and Purnima Chattopadhayya-Dutt. His works have been widely published in international and national professional journals and publications. A monograph “Bashirul Haq Architect,” which has extensively covered his works, was published in 2018.

He was conferred with the Lifetime Achievement Award in 2017 by the Berger Awards for Excellence in Architecture, administered by the Institute of Architects Bangladesh (IAB) and received the prestigious Hamidur Rahman Memorial Awards in 2018 administered by the Bengal Foundation.

Later in December 2017, a group of architects from Bangladesh, including Bashirul Haq, went to Basel, Switzerland, to attend the inauguration of the architectural exhibition “Bengal Stream: The Vibrant Architecture Scene of Bangladesh” held at the Swiss Architecture Museum. I remember the wonderful times we had with him and long walks together in the traditional streets of Basel.

I will always cherish all those fond memories with him.

Rest in peace, dear Bashir bhai.

Remembering Bashirul Haq

The news of the passing of Bashirul Haq (1942-2020), a much-admired architect of Bangladesh at a crisis time of the coronavirus pandemic brought not only sadness but also a feeling of helplessness in me. Losing someone close like him, whom I fondly called Bashir bhai, is difficult to reconcile with, but more difficult was the feeling of helplessness for not being able to go to his house, and offer my condolences to Firdous bhabi (Professor Firdous Azim) with whom I have an affectionate attachment. The first time Bashir Bhai and I met, it was the early 1980s when an elder brother of my friend got married to Bashir bhai’s sister-in-law, and the wedding ceremony took place at the under-construction site of Bashir bhai’s office cum residence at Indira Road. Architects’ office cum residence is still a rarity for Dhaka, and I hold fond memories of the tour he gave me showing his works, Kazi Khaleed Ashraf and probably few other friends present at that time.The tour undoubtedly was a fascinating experience for us at a time when we were still students of architecture, and we were quite attracted to the brick work and the vault construction. Bashir bhai in the early 80s had already established his reputation as an architect, and was quite well known. By then he had quite a few works to his credit that were well received with the public.

Interestingly my familiarity with his name in fact happened a few years earlier in 1977 when I visited his office at Dhanmondi to meet Badal bhai (Shafiul A.K. Eusufzai) to get some tips on freehand drawing for my architecture admission test. Although I did not get the chance to see Bashir bhai at that time, but I was very impressed by his neatly organised office that had opened within the same year. It must have been my first ever visit to an architect’s office. I remember a perspective drawing by Rab bhai (architect Abdur Rab) hanging on the wall. Rab bhai was involved in the competition entry of the BCIC office building at Motijheel.

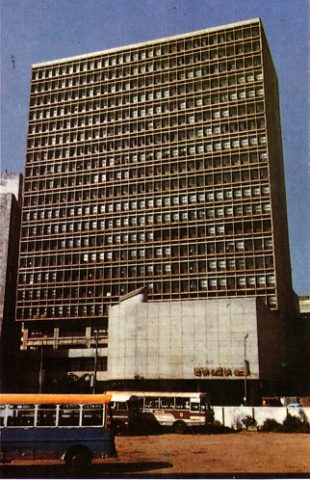

BCIC Bhaban, Motijhil, Dhaka, 1987. Photo: © Saif Ul Haque

My next memory of Bashir bhai is from a wooden model on display at BUET, and it was the model of the swimming pool he designed but never got built. Much later I got to know from Khokon bhai (Raziul Ahsan) that he was the one who made the model and how he enjoyed the task, and his time at Bashir bhai’s office.

Own residence, Indira Road, Dhaka, 1981. Photo: © Saif Ul Haque

Bashir bhai moved his office and his home from Dhanmondi to Indira Road after his office cum residence was built where he spent the rest of his life living, working, and offering a warm welcome to anyone interested to visit, and be his guest. His living room hosted many important meetings besides architecture, and his garden would host many dinners to guests from home and abroad. His residence became the temporary work and resting space for Susan Behr and Nathaniel Kahn when they came for the shooting of the film ‘My Architect’.

Bashir bhai studied architecture first at the National College of Arts (formerly Mayo College of Industrial Arts) at Lahore where he completed his studies by mid 60s. He later did his masters at the University of New Mexico in USA in 1975, and before going to New Mexico he worked with Muzharul Islam and Abdul Hakim Thariani, while doing a few works on his own.

He returned to Bangladesh in 1977, and as mentioned before he established his own practice Bashirul Haq and Associates (BHA). The office became an attractive destination for the recent graduates. I guess my frequenting to his office started when few of my class friends Asad (Badiuzzaman Rafiuddin Hossain), Neelu (Hasina Chowdhury) and Sheema (Nasima Jahan Khan) joined BHA practice after graduation in 1983. Also, a few of our seniors from Chetana, A.J.M. Alamgir, Uttam Kumar Saha and Rashidul Hassan were already working at BHA. The naturally lit and ventilated split-level workspace was a vibrant environment, and seeing all the well-drawn brick details were a delight.

Getting to know Bashir bhai more intimately was largely due to the affectionate relationship Khokon bhai enjoyed with him, and thus I could also share some of it whenever I was accompanying him or even visiting on my own. At times, we would turn up at really late hours, but his door was always open for us. Khokon bhai was the ‘enfant terrible’ to Bashir bhai and his wife Firdous. Khokon bhai got him introduced to Ali Joon Ispahani through Kaiser Rasheed Chowdhury that led to his subsequent commissioning for the developments of Free School Street Property Ltd. in Siddeshwari.

Bashir bhai, in his work, developed a very distinct language and vocabulary particularly in the use of brick and concrete that fused vernacular with modernity. The single-family residences executed early in his career, and apartment projects of different developers added to the well-established brick architecture of the country setting a high standard in construction. The competition winning entry for the office of Bangladesh Chemical Industries Corporation (BCIC) was a tropical solution for multistoried office building that echoed Lucio Costa, Oscar Niemyer and Le Corbusier’s ministry of education building at Rio de Janeiro.

Despite the fame of being an accomplished architect he as with many architects of the country, failed to secure any public projects due to faulty procedures unsympathetic to the engagement of architects. His works for non-governmental organizations like Gonoshasthaya Kendro, Nijera Kori, PRISM Bangladesh and DASCOH set examples of quality architecture with limited resources. His village retreat at Bhatshala can be considered as a contemporary expression of the traditional pavilion type dwelling of Bangladesh. The building for the cultural institution Chhayanaut in Dhaka has created a simple and intimate as well as an inspiring environment for carrying out programs of cultural education and performances.

Bashir bhai’s neatly designed and executed works have enriched the contemporary architecture of Bangladesh and carved out a particular position. His office provided inspiration and valuable learning experience to many aspiring practitioners. He kept himself free from getting involved in polemics, and remained devoted to the production of decent architectural works. The loss of a life that was so deeply intertwined with Bangladesh’s contemporary architecture will be strongly felt for a long time, creating a vacuum in many of our hearts that will take time to fill.

14th April, 2020

Bashirul Haq at BRAC University

On behalf of the Department of Architecture at BRAC University, Dhaka:

On behalf of the Department of Architecture at BRAC University, Dhaka:

Architect Bashirul Haq was an integral part of the Department of Architecture, BRAC University, from its very beginning. He became our permanent guide to the fourth-year housing studio for many a year. In the recent years he showed interest in teaching third-year studios where student exercises involved relatively complex design projects considering the total context of site, climate, structure, materials, forms and social aspects. These aspects were always emphasized in his teaching and profession. He was very much supportive of our community architecture studio. He appreciated the students of this studio who became sensitive to the needs of, and be more useful to the people in need. In his words, students need to think rationally without compromising on climate, culture, cost and spiritual dimension of the space.

On a personal note about never to compromise on site and climate, I remember my work experience in his firm. After staying abroad for a decade for studies and work, I returned to Dhaka, and was looking for a firm to start my professional career. I visited Bashirul Haq’s office, and the warmth of the brick building with profuse greenery all around, the lofty work space with a mezzanine level of architects’ offices complete with views and a balcony stole my heart. He tested me with the preliminary design of an apartment building. Later I heard that the colleagues were intrigued that he asked me to design something without giving me a sketch of his own ideas. As per my training, I took out my calculator, and started calculating how many apartments could I get for the site considering the setback, floor area ratio, etc., which kept me busy for a good part of the day, and also by which colleagues were surprised (1988). After the sketch drawings, he sat down to discuss the plan, elevations and sections. He said, ‘bring a butter paper’ (‘ekta butter paper aano’), and laid it over the plan. I was then made aware of the tropical sun and related shading, need for more ventilation, rain protection, and also the traditional bathroom fixture placements. I was happy that the plan did not change much, and that he guided me patiently in designing for the particular context. He made a newcomer welcome in the office. [Some of the colleagues said that him asking for a butter paper implied that he would probably come up with a completely new plan]. From then on, I started my journey of studying, and looking at buildings of the subcontinent, especially of warm-humid tropics. I visited almost all of his buildings in Dhaka, admired along with many aspects, the brickwork that he mastered so well. Later, one of his apartment buildings was part of my research that proved with empirical thermal data that a courtyard type apartment building performs much better environmentally than a non-courtyard one in the warm-humid Bangladesh. We also published Bashirul Haq Architect, a monograph on his work last year.

This year, he was teaching fifth-year studio in the Spring Semester. The students were really happy and inspired by his guidance, and since they were seniors, could absorb a lot from his critiques. Around the middle of the semester he became unwell, and so we created a ‘satellite studio’, where students went to his office once a week to get feedback on their projects.

Bashirul Haq was very precise in his critiques in design juries, which focused on the complete context, especially the climate. Students as well as teachers of BracU architecture learnt a lot from this ever-smiling teacher, mentor, guide and inspirer. Bashirul Haq is a person who we, and the architectural community of academia and profession will admire, and miss, a lot.

So it happened that the architecture of Bashirul Haq came to embody the most unlikely and lucky coincidences in the life of our families, and also, coincidentally, in my professional life as a landscape architecture and design scholar. There we were, in the calm and inviting, yet intricately interlaced rooms of the Indira Road residence, discussing architecture and urbanism, politics and poetry, but also looking forward to a common future. While our children had brought us together, initially there was already so much more, so many obvious explanations as to why our distinct paths had come to not only cross, but coincide. With contagious curiosity, Bashirul mapped them out, the affinities between the Scandinavian and Bengali architectural heritage, and made me think in new ways about the working-class masonry tradition of my south Swedish domicile. The red brick, a common denominator, filtered through Bashirul’s mind, and reflected through his context-sensitive architectural practice, and it would transform into a narrative material, bridging over distances and times.

And so it happened that under the canopy of his site-specific Bhatshala house on a warm and humid day in August, we came to discuss the potential significance of evergreen pine shrubbery, and melting snow mounds in the architecture of Aalto. And so it turned out that on a cool January afternoon in the light well of the Kalindi Apartment complex atrium, we would recall our respective stays at MIT, and our material encounters with the Baker House Dormitory. I brought him second hand books on Aalto that he had not seen, and we kept coming back to the possibility of visiting Helsinki and Jyväskylä together. Meanwhile, during Bashirul’s visits to Malmö, we settled for Sigurd Lewerentz, whose work would express the same kind of total artistic sensitivity as that of Bashirul, who in a similar way would treat every building as a complete work of art. I can still see him, pondering over conceptual structure, relational forms and material joints, as potential answers to the question of what it means to act in a world, the coincidences of which never cease to cause wonder.

Malmö 26 April 2020

Bengal Institute thanks all those who, in this difficult time, contributed to this Special Tribute to the departed architect Bashirul Haq. Bengal Institutes especially thanks Professor Firdous Azim, spouse of Bashirul Haq, and wishes her and the family solace in this time of loss.

15th April, 2020

Edited by: Kazi Khaleed Ashraf, Mohammad Tauheed, Farhat Afzal

Photos and drawings: © Bashirul Haq and Associates/as mentioned.

Video 1: © Bengal Institute and Swiss Architecture Museum, edited by: Muntakim Haque.

Video 2: © Bashirul Haq and Associates

Short link to this page for easy sharing: https://bit.ly/BHTribute