One of the main concerns of Bangladesh, home to 170 million people, is to strengthen food security for its people. The percentage of the country’s total arable land has been decreasing since 1989. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization’s report, the country had 73 percent arable land in 1989, which decreased to 59 percent in 2012. According to the Global Food Security Index, Bangladesh was ranked 83rd in 2019, the lowest among the South Asian countries. To improve the country’s position in terms of securing access to food, the government of Bangladesh has developed high-level policy initiatives, such as Vision 2021 and Perspective Plan. Such top-down tools and initiatives can only achieve their projected targets if the complex characteristics of the country’s diverse deltaic ecosystem is understood thoroughly, while acknowledging the value of ecosystem services.

Trends and Changes in Agricultural Practices

Shrinking of Farmland?

One of the key factors causing a loss of agricultural land worldwide is attributed to urbanisation. Economic expansion is often positively correlated to the loss of agricultural land. However, this expansion is not uniform in rural and urban areas, and this has led to an influx of people into the cities, especially in Dhaka city. It is estimated that in Bangladesh, about 1 percent of farmlands is being lost annually to non-agricultural activities. Agricultural land per capita has decreased by 50 percent in the last 25 years. In Dhaka, open and cultivable land has been converted to built-up areas, thus, decreasing agricultural land at an alarming rate.

Spatial pattern of farmland loss of Dhaka city and its peripheral areas; the maps show Dhaka city with 5 kilometres from the city boundary to understand the scenario of peri-urban areas

Due to rapid urbanisation, the loss of agricultural land has also been accompanied by a decrease in agricultural production inside the city. Therefore, a large proportion of the food requirements of city dwellers is met by production in peri-urban areas or rural areas at a much further distance. Agricultural production within the city is limited due to the lack of space, and therefore, agricultural activities are limited to small plantations, mostly on rooftops. According to Pramanik (2013), the types of urban agricultural activities can be divided into the following categories: rooftop gardening kitchen gardens, dairy, poultry and nursery production.

About 60 different species of fruits and vegetables can be grown in Bangladesh. The types and mix of these fruits on rooftop gardens are dependent on the availability of space, soil and local materials. There has been an increase in rooftop gardens in Dhaka city, which is attributed to the demand for organic food within the city. The demand has been driven by an attempt to make one’s own food, and by a decreasing reliance on the market, which has been marred with constant reports of adulteration of food. It has also been observed that small-scale miniature gardening in balconies of small apartments has also been on the rise.

Farming in and around Dhaka

The main driving forces for farmers in cities to become engaged in urban agriculture are food security and income generation. The urban agricultural markets are developing in response to growing demands inside the city; the demand for fruits and vegetables is increasing, which has led to the development of small farms in the city’s periphery. A similar trend is observed in response to livestock and poultry demands inside the city. A study conducted by United Nations Development Programme 1996 estimated the economic benefits of urban agriculture producers and found that Dhaka’s urban food producers are earning $500 per person monthly from urban food production, which was much higher than the poverty line. Therefore, the expansion of urban agriculture could pull a significant portion of the urban poor out of poverty.

Dairy production is considered to be the most feasible for the poverty-stricken population around the city. Milk from cows produces about $20 per cow monthly during the milking period. One thousand cattle farms have been established in areas surrounding Dhaka city, particularly in Dhaka’s outskirts of Keraniganj. Poultry production is set to increase many-fold in the future in Bangladesh. The slums are usually associated with some form of poultry production; the pattern of production varies significantly according to the density of the slums.

Nursery industry is booming in Dhaka city, and this can be observed in some parts of the city. According to a study by Mamun in 2018, about 74 percent of the private plant nurseries in the capital are established in government-owned lands. However, in the peri-urban areas of Gazipur and Savar, the nurseries are mostly established in rented properties. Kitchen garden production is prevalent in the urban poor population of Dhaka city, and this task is mostly carried out by women and children of the slums. There are instances of shared cropping and subsistence agriculture in the slums.

Awareness of the loss of farming culture: Who works?

There is a general lack of awareness of rights among farmers in Bangladesh, and a lack of self-organisation. There is also a general lack of awareness of the loss of farming culture in the city. In Bangladesh, there are three categories of organisations working for farmers’ rights. The first group are those influenced by external actors, such as NGOs, but they are not sustainable. There are also autonomous farming community organisations formed to establish farmers’ rights on a permanent basis. In between these two types of organisations, there are various small communities, associations and even firms that fight for the farmers. Most of the farmers’ organisations are small (20 to 50 members) and there are few organisations at the district, regional and national levels. Some autonomous farmers organisations are Adarsha Chashi Unnyan Samity (Model Farmers Development Organization), Andulbaria Multipurpose Vegetables Seed Production Cooperative Society Ltd., etc. The Bangladesh Agricultural Development Corporation, Integrated Crop Management Clubs and Union Farmers’ Associations (UNFAs) are organisations formed with governmental support. BRAC, ActionAid Bangladesh, CARE Bangladesh, Save the Children International and many NGOs have created farmers’ organisations working at the community level.

Climate Change: Farming and Displacement

Climate Change and the Food Situation

With multiplying impacts of climate change— increasing floods; cyclones; droughts—a variation of practising agriculture has been observed. Bangladesh is one of the worst affected countries of climate change. Since the majority of the population depends on agriculture, people need to shift their mode of farming. For example, the south-western part of the country has been affected by saltwater intrusion due to sea level rise and lower upstream flow. Therefore, rice cultivation has been hampered greatly. People involved in rice production needed to change their profession or change their mode of farming. Some of them do shrimp cultivation on the same land and some of them become carpenters or do other businesses. A vast population came to Dhaka and other large cities to upgrade their living standards. They have been losing their root of agricultural practices. The World Bank (2009) estimated that national rice production will decline in the period between 2005 and 2050, and that wheat will also be negatively affected by warming trends in the winter and pre-monsoon periods.

Food crops are under the threat of being wiped out by floods across major farming and agricultural lands. There are fears that the destruction of crops may lead to food shortages. Those most at risk include children, breastfeeding mothers, pregnant women and the elderly. There has not yet been any major food shortage scenario in recent decades, although severe cyclones and storms have been frequent. This is due to the government’s promptness in establishing food storage infrastructures. But the prediction says that low-lying countries like Bangladesh will have more serious climatic events in the near future and there will be an uncertainty in food security.

Displaced farmers: Loss of skills?

Displacement and migration have been the consequences of natural and anthropogenic phenomena. Usually, displaced people mean those who have been forced to live in other places from their roots. Bangladesh has had a serious number of internally displaced population. These people are mainly farmers, and they are usually displaced to other large cities. Dhaka has been one of the most popular cities for them for decades.

Some of the Displaced Farmers’ Profiles

Abdul Mazid, 64

“I have been in Dhaka for almost 20 years. I came from Rajshahi, a district in the north of the country. My parents were all farmers. Maybe I was too. As a kid, I did farming in the field with my father. But the terrible drought had been affecting our family. We were almost starving to death. Then, I decided to go to work in the city. So, I left farming and moved to Dhaka. I used to run a rickshaw. But as I get older, I can’t do it anymore. Now, I sell tea and cigarettes along this road. Yes, I left that farming life, and didn’t have a chance to be involved with it any further. My sons don’t think they will either. Actually, farming has no earnings here. The boys are making good income by working in the garments industry.”

Sobuj Miah, 49

“I’m a farmer. But now, I cannot do farming because there is nothing left on my farm. I came from Bagerhat. It is a district in the Southwest of Bangladesh. We used to grow rice from an early age. But with the increase of saltwater in the last 10 years, we can no longer cultivate paddy. We used to have a wide paddy field. As the salt comes up to the ground with the tidal water, everyone started to cultivate shrimp, not rice. But there is a need to invest some money in shrimp farming; I didn’t have much money, so I could not invest to grow shrimp. I came to Dhaka. I started to hire a rickshaw and started rickshaw pulling. This is a hard job, you know. I wish to collect some money and go to the village and start shrimp farming.”

Karim Ali, 55

“I came to Dhaka about twenty years ago. I used to do farming in the village before. But I did not get good prices while selling my products at the village market. For example, if I sold one kilogram of potatoes in the market, I would not get more than 5 Bangladeshi taka. The potatoes are sold in the city for about fifty Bangladeshi taka. I got very frustrated. I used to work so hard, but at what cost? I used to work from morning until evening. I needed to pay the labourers. At the end of the day, my investment would not break even. So, I left for Dhaka and started this vegetable business. There are many problems here too. I would like to go back to farming if the government gives more opportunities to farmers.”

Farmers have been displaced mainly due to natural factors, along with economic ones—natural factors include flooding, riverbank erosion, salt water intrusion and sea level rise, cyclones, etc. Once they have been displaced, they could never go back to their root profession, i.e., farming. For example, in most cases, due to natural calamities, farmers lose their farmlands and become helpless. They come to Dhaka and as there is no farmland in the city, they change their profession to rickshaw pullers and day labourers, small business owners, etc. Therefore, they lose their skills inherited from their ancestors—farming.

Food Flow

Food Demand and Supply

Bangladesh has nearly achieved food security in terms of rice production, the staple food in the country. Rice production has tripled over the last three decades. However, a report by the United Nation’s World Food Programme (WFP) in 2016 found that an alarmingly large number of people still lacks food security and remains hungry, and most people do not have a sufficiently nutritious and diverse diet. More than one in three children are still afflicted by stunted growth, and acute malnutrition has not decreased significantly over many years. The consumption of fruits and vegetables in Bangladesh is low and highly seasonal.

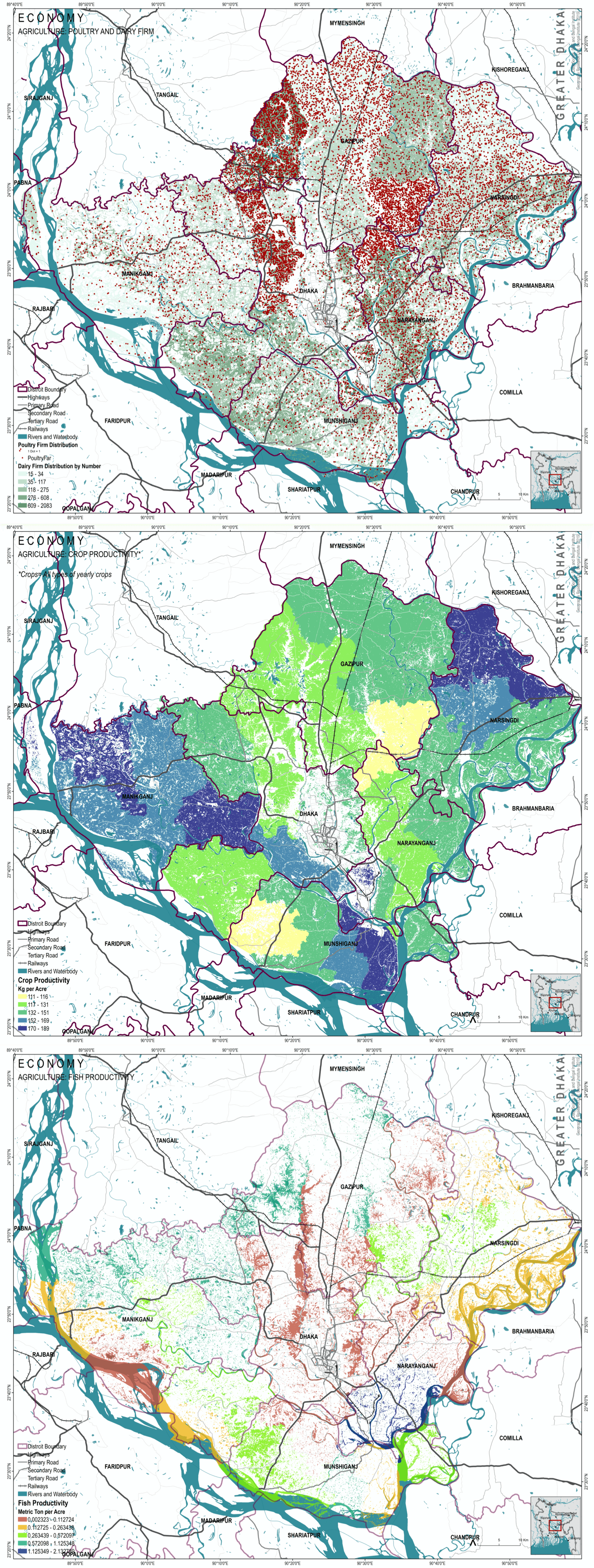

Maps showing distributional patterns of agricultural systems in and around Dhaka (from top: poultry and dairy farms; crop productivity; fish productivity)

Bangladesh mainly imports milled rice. India is the major source of rice import for Bangladesh, and other countries are Myanmar, Pakistan, Thailand and Vietnam. Bangladesh suffers from a severe agricultural trade deficit. In 2010, imports of agricultural products amounted to $6 billion or 19 percent of all imports, while they absorb 29 percent of earnings from all exports. In 2015, the amount of food import was 16 percent of the total imports. The value of food import spikes up significantly in years with high frequency of natural disasters.

Food Waste: Who and How Is It handled?

Dhaka produces approximately 5,000 tonnes of food waste daily. The people in Bangladesh are wasting about 5.5 percent of the total procured food. Of the total wastage, 3 percent is being made during procurement and preparation stages; 1.4 percent during serving; and another 1.1 percent from the plates (BIDS, 2016). Food and vegetable wastes constitute the highest proportion of solid wastes, varying from 70 to 80 percent. Yet, the solid waste collection is not separated based on the type of waste. Projections show that by 2050, the daily per capita waste will be 0.6 kilograms.

The waste collection system is divided into three parts. One is the formal waste collection by the authorities i.e., City Corporation; second, there is a community-based initiative to collect waste; and third, there are informal waste collectors, often called Tokais, who collect waste for recycling. Both the Dhaka North City Corporation (DNCC) and Dhaka South City Corporation (DSCC) are primarily responsible for collecting and managing waste in Dhaka. A significant amount of waste in Dhaka is not collected due to a lack of infrastructure, funds and collection vehicles. Despite the city’s limited waste management services, community-based door-to-door waste collection from households to local waste bins is considered a success. City corporation employees then take this waste to the landfill sites situated in Matuail and Amin Bazaar—two of the waste disposals sites near Dhaka. The pattern of waste collection in slum households is different to some extent. City Corporation, in general, does not provide any waste management services in these areas.

Some Photographs of one of Arfar Razi’s projects titled “Salinity Intrusion and Agricultural Productivity at the Coastal areas of Bangladesh”, 2017

Curtin University of Australia, Dhaka University’s Meteorology Department and Bangladesh Institute of International and Strategic Studies (BIISS) conducted a research and found out that the average temperature of Dhaka remains at about 2 degrees Celsius higher than that of the rural areas in summer and monsoon seasons. Only 2.7 percent of the total area in Dhaka is now protected as a green area. The rest of the terrain has been filled with various types of infrastructure. The city has only a total of 218 playing fields and 103 grass-covered open areas. So far, after independence, there have not been any more green areas like Ramna Park and Suhrawardy Park being established in Dhaka. Rather, settlements have been developed by filling up water reservoirs one by one.

Some of the Urban Farmers’ Profiles

Gayatri Saha, 57

“The idea of gardening at the rooftop with the empty spaces in front of my house came to my mind when I needed flowers for my regular prayers. Being a housewife and having enough space for gardening while living in government quarters, I started planting mostly flowers. Finally, when I got my own apartment building, I created garden areas on the rooftop. Slowly, I started growing fruits and small quantities of vegetables. I have almost five to six different types of flowers plucked from my garden for my morning prayers. It really makes me happy and motivates me to continue with my farming. This is in addition to small fresh herbs and vegetables like coriander, tomatoes and brinjal, which I often use for myself and my family (four members), and share them with my neighbours too. Most of my neighbours also do urban farming, and we often share our produce with each other, even if it’s in very small quantity. The biggest benefit for my family is the quality time we usually spend together on the roof almost every day while watering the plants. I don’t think I have plans to produce for commercial purposes in the near future.”

Monow Ara Begum, 60

“I am a retired school teacher. Being inspired by my mother, I started doing urban farming at the rooftop of my house from my childhood. I grow vegetables, flowers, fruits and some rare plants in my garden. I love to collect fresh vegetables and cook them. You know, our kitchen markets here in Dhaka have been filled with adulterated items. Besides consuming them with my family, I also distribute the fresh fruits and vegetables among my relatives.”

Kh Abdal Hossain, 40

“I am an architect and besides my profession, I have a passion for gardening. On my rooftop, I have a garden consisting of vegetables, flowers and fruit trees. You know, Dhaka city has a higher temperature than the peri-urban and rural areas. What I realised is that if we could plant trees in the empty spaces of our residences, the urban heat island effect will be mitigated. Besides, gardening gives me pleasure in many ways. I am not commercially growing produce from my garden. But, in the near future, I have a plan to produce commercially to serve people who want some fresh fruits and vegetables.”

Due to climate change, millions of people are coming to big cities every year, including the capital. As a result, cities need to be prepared for the settlement of more people. Emphasis should be placed on urbanisation designed to prevent city temperature rise. At the same time, legislation should be enforced to protect the city’s green areas and wetlands. Even though agriculture remains as the foundation on which the economy has grown, with around 62 million—or 40 percent of the entire workforce—employed in the sector, the sector’s contribution to overall GDP remains a mere 14 percent.

It is advisable to plant trees on the roofs and porches of the multi-storey buildings in the capital and to inspire micro-scale urban farmers as well. At the same time, it is urged that green areas and reservoirs in the capital be protected. In addition, if commercial buildings and factories have such green areas in their offices and establishments, they could be provided with tax relief. It is difficult to develop proper management of such numerous people in such a small amount of land. As a result, the green areas and reservoirs of this city have been destroyed, but effective steps have not been taken to protect them. However, plans have been put in place to protect all rivers and reservoirs in the Delta Plan by the government.

Author: Mohammad Arfar Razi

Maps and visuals: Bengal Institute’s Geography Research Unit

Photographs: Author, Nabila Binte Nasir

All profiles of the farmers with photographs are published with their permissions, and the published materials have been shared with them. This article was originally published on FuturArc, City Profile / 1st Quarter 2020. This version on Bengal Institute’s website has been slightly edited.