Tejgaon Church/Holy Rosary Church/Portuguese Church: AsiaNews

Tejgaon Church/Holy Rosary Church/Portuguese Church: AsiaNews

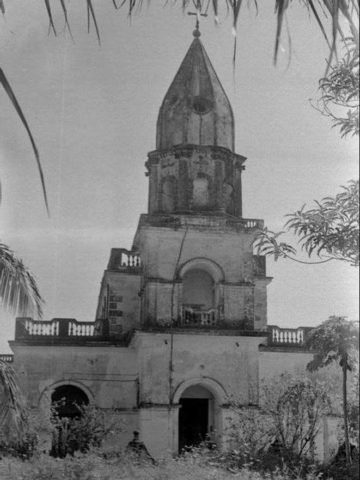

Tejgaon Church/Holy Rosary Church/Portuguese Church, Photo: A. M. Ahad, NaplesHerald

Tejgaon Church/Holy Rosary Church/Portuguese Church, Photo: A. M. Ahad, NaplesHerald

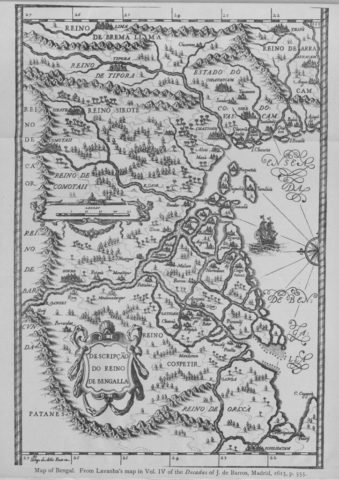

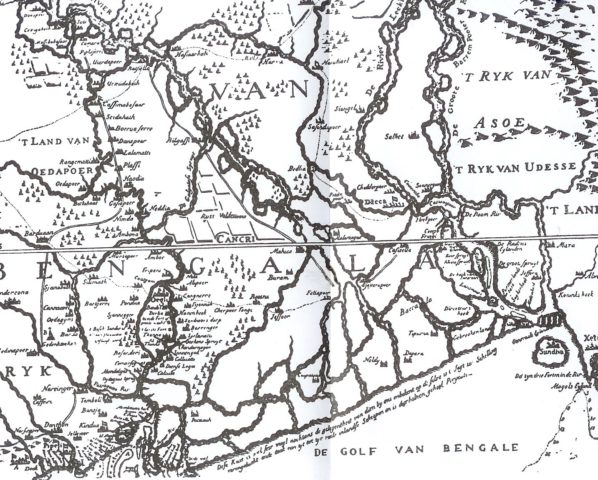

Barros, J. D. (1777). Asia. Dos feitos que os Portuguezes fizeram no conquista, e descubrimento das terras e mares do Oriente, 24, 1777-78. (First European Maps where Dhaka has been shown)

Barros, J. D. (1777). Asia. Dos feitos que os Portuguezes fizeram no conquista, e descubrimento das terras e mares do Oriente, 24, 1777-78. (First European Maps where Dhaka has been shown)

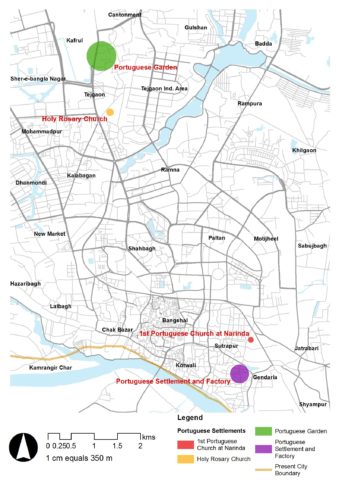

Location of the Portuguese Settlements and Structures in Dhaka, Image: Dhrubo Alam

Technically, the Portuguese were not only the first Europeans to arrive in Bengal but also in Dhaka. Already infamous for their piracy and other adventures on the coastal areas, Sundarbans, and along the big rivers, the Portuguese invoke various narratives in Bengal. We know from the descriptions of Portuguese missionary and traveller Fray Sebastien Manrique (1590-1669), who visited Dhaka in 1640, that there was a Magh raid in 1626 during which they (the Magh) had a few Portuguese working for their naval fleet[9]. The Portuguese in Dhaka are not to be confused with the ones who were engaged in piracy and pillaging together with the Maghs along the coast of Bengal, Swandip and Arakan (present day Myanmar). In Dhaka, the Portuguese were mostly missionaries and merchants coming primarily from their main base in Hooghly[3].

The church at Tejgaon, the oldest existing Portuguese structure in Dhaka, was thought to be built in 1599 by the Portuguese missionaries, as observed by James Taylor in 1840. He thought it was probably erected by the merchants even earlier, like the other older churches around the subcontinent[14]. Taylor was the civil surgeon of Dhaka district who compiled “Topography of Dhaka” with respect to the government guidelines issued in 1807.

According to some sources, the church at Tejgaon was perhaps built quite a few years later, in the early seventeenth century[4]. According to Ahmad Hasan Dani (writer of the Dacca: A Record of Its Changing Fortunes and curator of Dacca Museum in the 1950s) stated that the present church was built much later in 1677 (in 1679, according to the book, Glimpses of Old Dhaka, by Syed Muhammed Taifoor)[12]. Perhaps there was a Portuguese settlement in that area and a smaller church in the 1600s, as described by Basil Copleston Allen, an Indian Civil Service officer of Dhaka who produced the Dacca District Gazetteer of 1912, based on the travels of Ralph Fitch in 1586[6] and Francis Fernandez in 1599[7]. Fitch was a merchant from London. He was one of the earliest English travellers or traders to India and Southeast Asia, and Fernandez was the first Portuguese missionary in Bengal. This was the first documented proof of encounter with the Portuguese in the vicinity of Dhaka. According to Joaquim Joseph A. Campos (writer of the book Portuguese in Bengal, 1919), they settled here in 1580. Although the Portuguese were rebels against Emperor Akbar at that time, they bought two villages in Bhowal, and most importantly bought a piece of land in present day Narinda[2]. They definitely built a church in Narinda in the early 17th century. Today, there is no trace of that church, probably the first church in Dhaka, but most likely it was situated at the site of the Christian cemetery. The Portuguese officially established a mission in Dhaka in 1616, about 50 years before the viceroyalty of Shaista Khan (1664–1688).

In 1632, Emperor Shahjahan was outraged by the human trafficking, unabated trade, heavy armament of forts, and the power of the naval fleets of the Portuguese, and started to drive them out of Bengal (with the siege of Hooghly). The church in Narinda was abandoned during this period but was not damaged, as both Tavernier and Manucci found when they came to the city[1,8]. Jean-Baptiste Tavernier was a French gem merchant and traveller, and Niccolao Manucci was an Italian writer and traveller, who worked in the Mughal court. They were both from the 17th century, and visited Dhaka in the 1660s. The Portuguese had recovered very well through shifting their political allegiance to the Mughals. In his conquest of Chittagong from the Arakanis (1665–1666), Shaista Khan even received 40 ships from them for his naval fleet. In return he allowed a Portuguese settlement and trading post on the bank of Ichamoti river (about 25 km south of Dhaka) at the present day

Muktarpur–Mirkadim area, Munshiganj, which still bears its historical name of ‘Firingibazar’ [2].

The Portuguese were mainly involved in the salt trade. Father Anthony Barbier in his visit to Dhaka in 1713, spent the Christmas at the church at Narinda. But in 1789, the only church mentioned in documents was the one at Tejgaon, then a village four miles north of Dhaka’s centre. Apparently, the church at Narinda had been deserted by this time and the activities had been shifted to Tejgaon[7]. Nonetheless, the Portuguese settlers in Dhaka were still at the proximity of the old church (present day Narinda-Laxmibazar-Banglabazar area), as seen in Rennell’s map (1780)[9].

Major James Rennell, was an English geographer, historian and pioneer of oceanography. He produced some of the first accurate maps of Bengal. The Portuguese had a factory in Sangattola, in close proximity to present Banglabazar used for trading purposes like other European trading communities. The headquarters was there even in 1905, although in ruins by then, as described by Francis Bradley-Birt (1914)[10]. Bradley-Birt, diplomat and writer, an English member of the Indian Civil Service, was stationed in Dhaka for a while and published The Romance of an Eastern Capital as his accounts of the city. A Portuguese garden north of the Tejgaon church was also depicted in the map[9].

The Portuguese essentially paved the way for other European traders for doing business in Bengal. They were the first, and as a result had to wrestle their way into Bengal, clashing not only with the Mughals, but also with Pathans and Arakanis. The two main reasons for their decline were competition from other European trading powers and the initial hostility between them and the Mughals. Other European powers started to receive firman (a grant or permit) for trading from the Mughals from the 1620s. Each European power wanted to create a trade monopoly and the competition between them was toxic.

The siege and ransacking of Hooghli in 1632 by the Mughals dealt a severe blow to the Portuguese. After that, becoming an ally of the Mughals in 1665 proved to be fatal for the Portuguese, since the Mughals started losing power to the English in the eighteenth century. Moreover, when the Portuguese joined the Mughal army and naval forces, they had stopped raiding the coast of Bengal, and were even engaged in protecting their fellow countrymen from piracy and plunder. Most of them became merchants, and few became mercenaries. They were no longer a political or military force.

After giving up their political entity and integrating as common people, they survived as tradesmen even in 18th century Dhaka, as depicted in Rennell’s map (1780). But slowly, they lost their footing in business to others, first to the Dutch, then to the English, almost within a century (1665–1765). By the early 18th century they did not possess any real financial power to overthrow the Dutch of their trading supremacy in Bengal. It is unknown when the Portuguese factory was closed down in Dhaka, though their missionaries established another church in Dhaka district in 1815. These churches, the names of some places where they settled and the epitaphs in the cemeteries are the last reminisces of the Portuguese in Dhaka.

Armenian Church, Dhaka, Photos: Mohammad Tauheed CC BY-NC

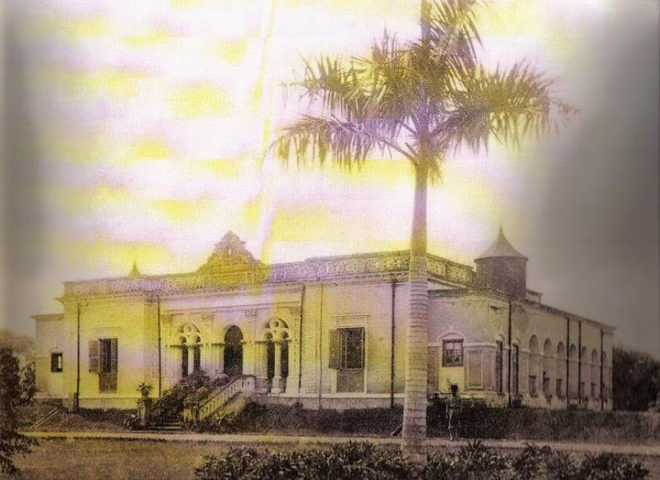

Photographic Album of Old Dhaka, published by Bangladesh National Museum (February, 2012, 2nd Ed.) (inside present day Banga Bhaban)

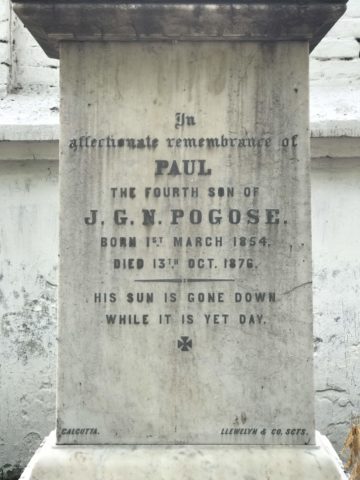

Epitaph of Pogose’s 4th son, Paul, Photo: Fatiha Polin

Epitaph of Pogose’s 4th son, Paul, Photo: Fatiha Polin

Grave of Margar David’s (the merchant prince of East Bengal) wife, Elizabeth, Photo: Dhrubo Alam

Grave of Margar David’s (the merchant prince of East Bengal) wife, Elizabeth, Photo: Dhrubo Alam

Armenian Church in 1965, Photo: Roger Gwynn

The Armenians most probably came to Bengal even before any other European merchants, and played an important part in the export-import business of not only Bengal but also India. But, it was in Bengal where they were most active. They reached Bengal-Bihar in the early 17th century if not earlier, as there are inscriptions (now preserved in Kolkata Museum) found in Bihar which dates back to 1630-1640s[11].

According to Dani, Armenians settled and founded a colony in Dhaka in the early part of the 18th century at Tejgaon based on the fact that graves of some Armenians who died between 1714 and 1795, were found in the Portuguese church[4,12]. On the contrary, Anne Basil (writer of the book Armenian Settlements) states that the first Armenian traders of Dhaka are reported to have reached the city in 1613[11]. In addition, a letter from the company in London to Mumbai in 1689 asked the English company to help the Armenians while procuring clothes, raw silk and other fine goods from Bengal, including Dhaka as they had a better trade network, capital, logistics and connections that included their homeland, Julfa in Persia (Iran). It is said that, they settled in Saidabad (a locality in the vicinity of Murshidabad, in present day West Bengal) after getting permission (firman) from emperor Aurangzeb in 1665, and also built a church there[1,4]. There is a grave of a lady in the Armenian church in Kolkata (established in 1724) bearing the date 1630. So, it can be said that even if they did not settle in Dhaka in the 17th century, they certainly had their business and trade network in this part of Bengal.

The Armenians settled in the present day Armanitola, still bearing trace of their presence in the name of the locality. They were at first a small community but were unmatchable in textile trading and in some cases had monopoly in saltpetre, betelnut, opium and salt trades. According to James Taylor, in 1747, Armenians were the largest exporter of Dhaka cloth, far ahead of English, Dutch or French companies[14]. With these profits and huge resources, they became very influential and rich, resulting in the construction of a church of their own and other private mansions.

Prior to the construction of the present church in Armanitola, they worshipped at a small chapel which they had built in the same locality. In 1781, the present beautiful church of the Holy Resurrection was erected on the site of the old chapel, by subscriptions from Michael Sarkies, Astwasatoor Gavork, (George) Margar Pogose and Khojah Petrus. In 1837, a beautiful steeple, which was to serve as a clock-tower, was erected on the west of the church, near the belfry, but it fell down during the severe earthquake in 1897. There was an oil painting of the bishop in the Dacca Armenian Church, by a well-known European artist, but it was taken away by the Archbishop Sahak Ayvadian in 1907[4,7].

The Armenians were famous as a merchant from ancient times, and their main philosophy was to get involved with any business which brings profit. They have brought the jute business here in the second half on 19th century. They were the pioneers in jute trades, the name of 12 eminent merchants of Bengal engaged in jute trading in Dhaka and Narayanganj in the late 19th and early 20th century can be found. Some of the most prominents were Abraham Pogose, Margar David, J. C. Sarkies, M. Catchatoor, A. Thomas, J.G.N. Pogose, Michael Sarkies and P. Aratoon. Among them, M. David & Co. was so advanced that they sometimes bypassed Kolkata and started to export jute direct to London through Chittagong. They also owned 12 motor launches which carried goods. Other than the jute trade, Armenians were also involved in internal trading and local logistical support because of their huge trade network[7].

Also the Armenians introduced hackney carriages (টিক্কা গাড়ি) in Dhaka. The founder of the G. M. Shircore & Sons, Mr. Shircore brought them to Dhaka, and it was the first means of public transport in the city. It became such a success many other Armenian and local businessmen followed suit. The Armenians were the first to introduce European and British goods in the city and setting up departmental stores similar to those of today. C. J. Manook, G. M. Shircore etc. were few of the businessmen in this business. Incidentally, these stores provided the supply of tea in those days and popularised it as a drink to the elites[7].

An interesting case was that the Armenians were always competing with the English so they have to explore many businesses to start from scratch and at one time they started to buy ‘Zamindari’ unlike any other places in India. There were only three Armenian zamindars in 1836-38, paying more than 1,000 rupees a year, but their number grew rapidly in the later half of that century. Families of Michael, Sarkies, Aratoon, Stephens, Lazarus, etc., became zamindars. Khoja Michael, Aratoon and Lucas were the zamindars of South Shahbazpur (Bhola), Pargana Hussain Shahi and Doulat Khan respectively.

The Armenian community contributed a lot to the civil society and the life of the city. Nicholas Pogos in the early 19th century established the Pogos School, which was only one of the three English school in Dhaka back then. He was also a founder member of the Dhaka Municipality (established in 1864) and was active for a long time. Furthermore, they had a big impact not only in Dhaka but also neighbouring towns, e. g., Narayanganj, Mymensingh. Herbert Michael Shircore, son of Stephen Aratoon Shircore, became the chairman of Narayanganj Municipality. Presently a school and a road is named after him.

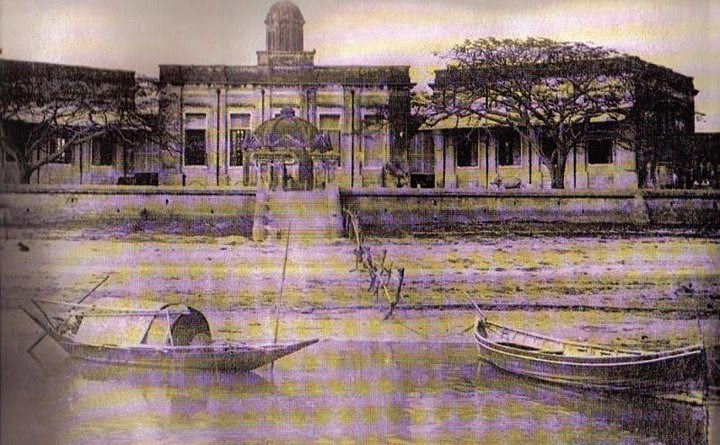

Location of Dutch Trading Post in Dhaka, which has become Mitford Hospital in 18th century, Photographic Album of Old Dhaka, published by Bangladesh National Museum (February, 2012, 2nd Ed.)

Location of Dutch Trading Post in Dhaka, which has become Mitford Hospital in 18th century, Photographic Album of Old Dhaka, published by Bangladesh National Museum (February, 2012, 2nd Ed.)

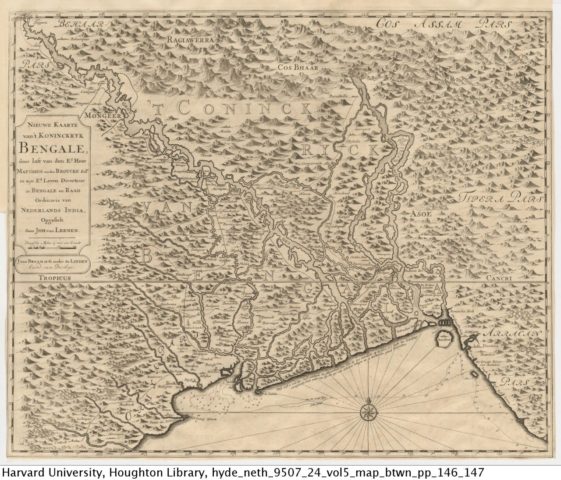

Map of Bengale, Valentijn, François (1724). ud en Nieuw Oost-Indiën (in Dutch). Te Dordrecht: By Joannes van Braam.

Map of Bengale, Valentijn, François (1724). ud en Nieuw Oost-Indiën (in Dutch). Te Dordrecht: By Joannes van Braam.

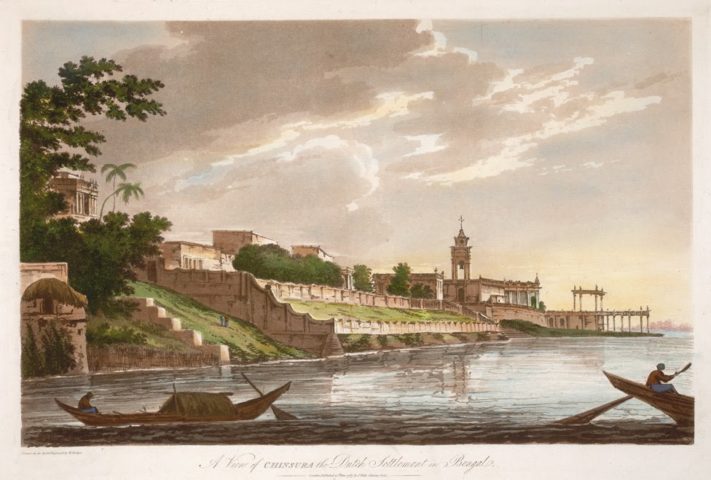

Plan of Dutch Factory at Chinsura, Hooghly (1721)

Plan of Dutch Factory at Chinsura, Hooghly (1721)

Dutch settlement at Chinsura in 1781/82, Plate 28 from William Hodges’ Select Views in India

Van de Brook’s map of Bengal (1660)

Van de Brook’s map of Bengal (1660)

“Carannigons” (Keraniganj) and “Damerah” (Demra), c. 18th century (National Archives, The Hague: Vosmaer family map collection (access code 4.VMF), inv. no. 848, plate 36, f. 46).

“Carannigons” (Keraniganj) and “Damerah” (Demra), c. 18th century (National Archives, The Hague: Vosmaer family map collection (access code 4.VMF), inv. no. 848, plate 36, f. 46).

Dutch V.O.C. factory in Hoegly (Hooghly-Chuchura, Bengal) (Hendrik van Schuylenburgh, 1665)

Dutch V.O.C. factory in Hoegly (Hooghly-Chuchura, Bengal) (Hendrik van Schuylenburgh, 1665)

India has always been deemed as a heaven for various businesses to the European traders. For ages it has been renowned for its prosperity and has been popular for spices. Since 15th century European traders started to appear in the Indian Ocean and the subcontinent apart from the traders from Arab, Iran or China. First came the Portuguese, afterwards, more than a century later came the Dutch. We generally called them ‘Olondaj’ in Bengali (comes from the word ‘Hollandia’). In 1602 few Dutch businessmen founded Dutch East India Company (Dutch: Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie, VOC, ‘United East India Company’ in English) in order to establish trade routes and links with the orient (defunct in 1799)[5].

In a short period of time, the Dutch could expand to various corners of the world, especially in East Asia and South Africa. They reached Bengal in 1607, but settled and built a trading post in Chinsura, Hooghly a bit later in 1635 after getting a firman from the Mughal ‘subedar’ (governor). As a matter of fact, the Dutch governor of Coromandel (present day Karnataka in South India) sent few persons to set up a trade centre in Bengal[5]. On the other hand, the Dutch were probably involved in piracy and slave trading like the Portuguese in the 1620s along the Bengal coastline.

One after another, they started to set up trading posts at different locations in India, one of which was Dhaka. They came to Dhaka for the first time in 1636, but it was a tragic experience for them. It was supposed to be a diplomatic mission consisting of six people, but even before starting from Hooghly, the had some altercation with the local authorities and were arrested. They reached Dhaka in handcuffs. They could get their freedom from the Mughal court in Dhaka, but had to pay handsomely to provide some gifts for the Nawab. They had to pay for the transportation cost and bear the payment to the blacksmith in order to break the handcuffs too. Moreover, they were beaten up and badly bruised, and had to be treated by doctors. So, they had to pay additional medical bills. The situation was so hostile that, they had to buy a boat and pay for the boatmen while going back to Hooghly. It cost them more than a thousand taka, which was a huge sum back in those days. The only achievement for them was a trade agreement with the Nawab[1,5].

Their settlement in Dhaka was neither established nor did they have a stronghold following this incident. They again tried to set up a trade centre here in 1666. They contacted an official of Nawab’s court named Rajendralal to create a favourable situation. They also appointed a Bengali-speaking assistant Gangaram in their factory. They did not trust any of the natives because of their past unfortunate events and bitter experiences. Nevertheless, the Dutch established trading houses, offices, factories and gardens gradually in Dhaka since 1660s and they were in operation till 1785[5].

The Dutch factory that was located by the Buriganga River, at the site of present day Mitford Hospital, was also their office[7]. Also, they had a garden in the vicinity of Farmgate, probably in between present day Ananda Cinema Hall and Tejturi Bazar area. These locations can be found from the map of Major Rennell (1781)[8]. The trade post of Dhaka was under direct control of the trade center of Chinsura, Hooghly. That centre was operating under supervision of the Dutch trading office of Coromandel. The main centre for business and trade office for the Dutch in Southeast Asia was situated in Jakarta, Batavia (present day Indonesia). In the end, their factory in Chinsura, Hooghly of Bengal came under direct control of Batavia, as its importance gradually grew[5].

François Bernier, a French traveller who visited Dhaka in 1665-1666, stated that the Dutch had a monopoly over cloth export from Dhaka[6]. They generally exported to Europe and Japan. Their other main export item was Saltpetre or Nitre (locally known as ‘Sora’) which was one of the main ingredients for producing gunpowder. They used to collect huge amounts of Saltpetre mainly from Bihar and set up a refinery there[5]. Also in the same time period (1660s), Tavernier saw a beautiful warehouse of the Dutch in Dhaka[13].

In many businesses the Dutch were the pioneers and frontrunners. They even got a ‘farman’ in 1746 that only the Dutch would be allowed to export opium from Bengal. At the same decade, the British trading power started to gain ground, and their main competitor were the Dutch. Inevitably this struggle for supremacy and profit, led to serious confrontations. In 1759, the Battle of Chinsura took place between the Dutch and British, in which the Dutch lost decisively, even though they possessed almost similar naval power[5]. In reality, the British had already cornered all the other European powers in Bengal, after their most important victory in the Battle of Plassey (1757). As a result, the Dutch have never regained their financial or political upperhand after 1759, despite their presence in Dhaka or Bengal.

Eventually, during 1781-1783 the British took possession of all the Dutch trading centres and posts. The one at Dhaka surrendered in 1781 and the Dutch garden at Farmgate was also handed over. Virtually their business in the city ended at that time. The Magistrate transferred the house (Dutch Trade office) to the Collector of Dhaka in 1801 and the authorities demolished it with help from the Police [1]. The rubble was used for repairing roads of the city. In 1810, the authorities proposed a hospital at that site (the present Mitford Hospital)[7]. Finally in 1824, the Dutch government handed over all their belongings in India to their British counterpart, according to a treaty between them. With the official transfer happening in June, 1825, the Dutch left Dhaka, Bengal and India for good[5].

The British deliberately tried to remove all their political and business competitors by any means, and they were very successful in doing so. Mostly as a display of power, they destroyed the nice trading house of the Dutch in Dhaka, which was already more than a century old by then, and repaired the roads with its debris. There is no evidence of the Dutch Garden at the present day Farmgate area, other than the depictions of it in the old maps of the city. However, when the chief of the Dutch Factory in the city, Mr. Langkheet died in 1775, he was buried in the then English Cemetery (now at Narinda). At present, this is the only remaining sign of the Dutch in Dhaka[4].

References

Roy, Ashim Kumar. 2016. Banga Brittanta [in Bengali]. Dhaka: Dibyaprakash.

Taylor, James. 1840. A Sketch of the Topography & Statistics of Dacca. Calcutta: GH Huttmann, Military Orphan Press.

This article is from the upcoming issue of VAS. Click here to see the previous issues. Short link to this page for easy sharing: http://bit.ly/Vas4Europeans