The recent government decision to invite foreign capital for building affordable housing is welcome news for one primary reason, that we have failed miserably in addressing the housing needs of a vast majority, the limited income groups. Our housing institutions, and the platoon of housing experts have not been able to provide any notable model of how we should live as a group in new urban conditions.

A Daily Star editorial (January 7, 1999) lauded the government decision as significant and sensible. The same editorial also sounded five fair and reasonable warnings. The Daily Star pointed out that the low-cost “flats” must not be sub-standard, that the ownership and transfer rules must be regularised, that areas and facilities for common use must be properly managed, that there must be a code for living in “flats,” and that the housing complexes need to be well connected with the greater urban facilities. These are all points which, if not addressed well, may lead to the deterioration of the housing. But, has enough been pointed out here?

Housing is a key issue in any developmental context. As the Aga Khan, a leader in some major architectural and development initiatives, noted: “The lack, and the deterioration of human habitations, as economics grow, urbanisation accelerates and demographics explodes, pose some of the greatest practical and ethical problems that developing countries face… In the seamless web we call national development; housing is only one factor influencing the quality of human life. But how vital it is to health and human safety. Still more fundamentally, the state of a person’s home touches deep chords in the human spirit. Housing is not just a numerical and fiscal matter. The key issue is the human spirit.” Housing is not just a numerical and fiscal matter, the key issue is the human spirit.

The architecture of housing does not imply “looks” as architecture, unfortunately, has come to mean, but how spaces (rooms) within the units of the housing, and spaces that make up the public domain are knit together in a harmonious fabric. And, eventually, how this well-knit fabric is linked with the larger urban structure, to its streets, its various institutions and resources. It is this set of relationships that could affect the human spirit – touch a chord or disrupt it.

There is reciprocal relationship between housing complexes and the city. On the one hand, a city is made up of the aggregation of housings. On the other hand, the web of spaces in a housing reflects a miniature city. How we define and frame housing is how we see our cities and vice versa. One reason for Dhaka’s current chaotic condition is we have not been able to create new and suitable residential models for the many different communities that inhabit it. There is either poor planning, or too much uncontrolled growth.

It does not need an Amartya Sen to tell us how the situation is, and, by the way, he is absolutely right in not recommending anyone to live in Dhaka, including Gulshan or Banani. The situation is, by any standard, is pretty grim.

We would then like to add a sixth, in fact, a vital item to The Daily Star list of concerns: housing must be conceived as enhancing the quality of life, both the life of the immediate dwellers and the life of the city.

The housing issue is two-fold: numerical and environmental. Numerical implies a statistical concern, something which is fact-based, and understood by most of us immediately. It includes issues like housing back-log: how many people are migrating to the city each year and how many dwelling units are available through various mechanisms – public, private and corporate. There is no doubt a massive numerical urgency in Dhaka: the total need is far greater than what is decently available. However, overwhelming and pressing the numbers seem to be, this should not keep out of the focus something which is generally not easily measurable: the cultural, environmental and human side of the issue.

The key concern is: how can the physical and spatial fabric of the housing enable the cultural and collective life of the inhabitants? This is often a vague matter, but it is the most essential aspect of housing. There are innumerable examples from all over the world of well-intentioned housing complexes that were vandalized, abandoned, or altered because it came in conflict with the societal and cultural values of the inhabitants. A successful housing, for whatever income group it may be (but especially for limited income groups), is one where the physical fabric amplifies and not inhibits the social fabric, that is, the collective and community life. Numbers do not make housing, eventually it is people and their life that matters.

Charles Correa, the eminent Indian architect, has spoken eloquently in this regard about the significance of two things: (1) the necessity of open-to-sky spaces in tropical conditions, a necessity arising out of a social, pragmatic, psychological, and even spiritual reason, and (2) the intricate, and often invisible, chain that is formed from the inner sanctum of a house to the public, community space. Almost every community makes a chain stretching from the innermost private space to that gathering space that could be the tree in the chowk, or court of a mosque. A variety of open and semi-open spaces form the rest of the chain. It might include the veranda of a house or just the front steps, the neighbourhood street, the street corner with a shop or two, the elementary school with It forecourt, the playground, etc.

The most important decision, however, is the selection of the building type. It is not at all useful to jump to the “flat” type; the “flat” is just one of a kind among many dwelling types, Including rowhouses, semi-detached houses, or even independent houses. All type should be considered to see what each offers in terms of the nature of arrangement of “rooms” in the unit, and what impact each type can have on the overall – social and spatial – fabric of the housing. It is expected that many of the target inhabitants of the lower income group will have come from rural areas, or will still be maintaining a strong tie with the villages. How to provide a setting for their lives in an urban context?

There are a number of strategies here. In most cases, the primary success of a housing lies in the selection of dwelling types, and how the dwellings are arranged to create a social and spatial fabric for a particular group. The task of the architect and the planner is to make that crucial selection. Again in many cases decisions about types and the nature of the fabric may be taken in close conversation with the potential Inhabitants. A good example of that is the work of the legendary Egyptian architect Hasan Fathy.

It should be acknowledged honestly that we have done poorly in the area of large-scale housing, public or affordable. The low and limited income groups have been completely ignored in our housing visions. Whatever there is, even the public sector housing, catering to government and corporation employees has no exemplary models, despite the undeniable fact that quite a large number of housing complexes have been built all over Bangladesh on the last twenty-five years. Azimpur housing, one of the earliest models of mass housing in Dhaka (1949), and others that have followed it, are examples of a wasteland. They are characterized by a run-of-the-mill plans where flats are stacked like pigeon holes, and building are placed in barrack-like formation with no or little articulation of public spaces. Such models have been proven to be quite inadequate and unimaginative, yet are still touted by some of our planners, as can be seen in such reincarnations as the T&T Colony (and all such colonies), the so-called “Bailey Dump” housing, and many others.

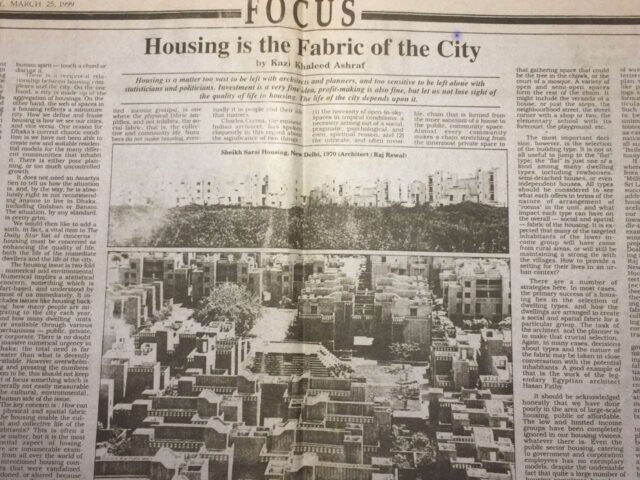

If we must learn from elsewhere how to handle numbers, from China or Singapore, or the “million houses programme” in Sri Lanka, we must also look at successful examples of how to address the quality of life in housing. There are a number of acclaimed housing projects in our region from those geared towards limited income to middle income groups. There is, for example, the Aga Khan Award winning low-income housing project in Indore by Balkrishna Doshi, the Anguri Bagh housing in Karachi by Yasmeen Lari, Raj Rewal’s Asiad village in New Delhi, and the Shustar Housing by the Iranian architect Kamran Diba. All those project provide standard dwellings, but more than that they speak about the intertwining of the spatial and social fabrics; the enhancement of the collective life, the strengthening of the economic life, and the continuation and innovation of tradition.

It might be profitable for the government to set up a commission to study different housing fabrics, to see which kind of fabric offers what kind of spatial and social matrix, population density, growth potential, common facilities, traditional situations, etc. The result of the study then could be recommended to the decision-makers, and to the investment and building groups.

Housing is a matter too vast to be left with architects and planners, and too sensitive to be left alone with statisticians and politicians. Investment is a very fine idea, profit-making is also fine, but let us not lose sight of the quality of life in housing. The life of the city depends upon it.

By Kazi Khaleed Ashraf

Originally published on The Daily Star, 25th March, 1999