Sadarghat is where it all started, more or less. The city of Dhaka began a love story there with the river which became the social, economic and cultural foundation of the city. If an area in the city displayed some semblance of a “designed” or “decent” urban space linking the river, that too was Sadarghat. The phrase “Buriganga is the lifeline of the city” gathered meaning in the above context. But much water has flowed along its banks, of which most is now unholy effluence, sewage and pollutants. It’s a love story that has gone awry. Now, Sadarghat is an emblem of the rape of the river and its banks. With vanishing riverbanks, and even vanishing aquatic life (thanks to our toxic gift to the river), we are close to declaring the river as near as dead. The savaging of Sadarghat is symptomatic of our overall apathy to make our collective lives better, our pathological inclination to commit self-mutilation.

Sadarghat may be the original urban riverbank but now it is one of many. The riverbanks of Dhaka describe a diversity of habitations and territorial conditions along their various edges. They shows a high degree of urbanity at places like Sadarghat, agricultural and wetland landscape at many points east and west of the city, and haphazard built-ups at places like Gabtali and Tongi Bridge area. A broad development plan — what is described as a master plan — for Dhaka must consider that diversity. Urban design approaches are much more precise and definitive, and need to respond to specific locales and conditions while at the same time connecting to the larger plan. Sadarghat dearly awaits an urban design intervention that will renovate that area and also at the same time be a catalyst for the overall resuscitation of Dhaka’s riverbanks. There are many reasons to target Sadarghat. First of all, it’s where it all began; it represents the original vibrancy of the city. If we can show the audacity and boldness to recover the original river landscape of the city and transform it in tune with the spirit of the time, we can certainly re-address the rest of Dhaka’s riverbanks. The reason Dhaka’s urban ills keep proliferating with no end in sight is because the city has not witnessed any viable and inspiring urban design model. With no alternative in sight, and no visionary example to point to, the only option left for the city is self-mutilation. And that is another urgent reason to consider a major urban design intervention at Sadarghat.

It’s not too well remembered now that the first urban design workshop on the Dhaka riverbanks was organised by Chetana Architecture Research Society and The Daily Star back in 1999. Some of the conclusions and propositions made at that workshop are still relevant. At that time, 5 teams of architects worked together for three days on the Sadarghat area and came up with idea plans with drawings, sketches and models. The result was presented at a public forum. The rallying call made at that time was: We need to save the rivers to save Dhaka. Now some ten years later, that cry is still being heard but only that the crisis has become near catastrophic and the need more urgent attention.

It’s not acceptable to think that the recovery and reconstruction of Dhaka’s riverbanks is an impossible dream, and something that will never come to be realised. Such defeatist thinking is a clever ploy to let things stay as they are when there are many cases around the world — from New York City to Istanbul and Seoul — where far more critical and complex urban conditions have been turned around by enlightened city leaders, committed citizens, and some bold urban design moves.

The 1999 workshop concluded that a Sadarghat Riverfront Development could be a catalyst for an economic and social rejuvenation of not just old Dhaka but the whole city. It was obvious that Sadarghat remains one of the most dynamic areas in Dhaka, but its fullest potential has not yet been realised. In fact, from being a historic civic space and an energetic urban place, the area has now become the symbol of sharp physical, social and environmental deterioration. Once part of a gracious public space, Sadarghat has now been ruthlessly mutilated. If we are capable of doing this to the site of the origin of our city, it confirms how deep our civic insensibility and urban illiteracy are.

The reality is that Sadarghat need not be like a gigantic garbage pile. With thoughtful and imaginative planning, and I daresay bold ones, Sadarghat could be transformed into something befitting the riverfront of any civilised city. By being so, it could provide renewed recreational, civic, economic, and transport facilities not experienced before. And not just for the citizens of the area but for the whole city. And not just in recreational and aesthetic terms, but economic as well. This transformation could be effected through a set of careful urban design and architectural strategies.

We revisit some of the ideas proposed for such a possible future:

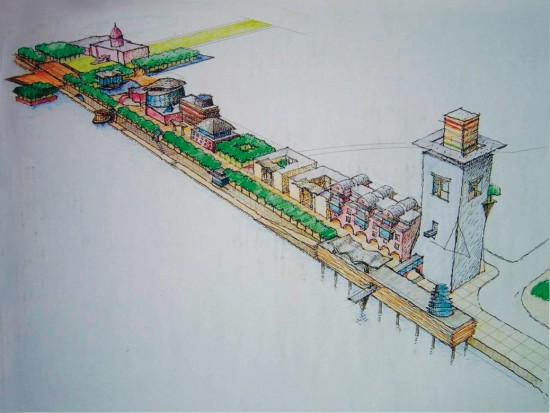

Sadarghat as a riverfront district

A “riverfront district” can be designated with Sadarghat as the epicentre for the purpose of producing and maintaining a clean river, a decent riverfront and a sustainable and exemplary riverfront district enjoyable and accessible to everyone. The district will be a site of model public spaces and public buildings. Innovative building types will have to be conceived that conform to the river and canal-front conditions. A Riverfront District Authority may be established that will be responsible for the management of the designated district which will also include its social and economic development. Since the intervention will be in a dense, existing community, a consensus will have to develop with local citizens and stakeholders that something far more superior can be achieved in the area. The Riverfront Authority, with special support from the government, could form innovative partnerships with both city organisations and private groups for various projects and programs.

The riverbank as a civic realm

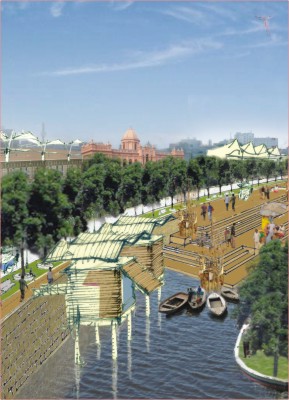

The riverbanks need to be returned to the city. It cannot be overemphasised that the crown in the district is the riverbank. The principal and single-minded aim of the enterprise would be to bring the people to the riverbanks. Currently, even the immediate residents of Old Dhaka are exiled from the banks of the river as every nook and cranny is occupied by all kinds of unwholesome and unruly activities. To return the riverbank to the city would simply mean that the banks (to a certain clear width) should be decreed as public space allowing uninterrupted access for people where no private encroachment and building of any sort will be allowed (unless authorised by a special expert body belonging to the Riverfront Authority). The whole length of the riverbank in the district should be developed as a tree-shaded promenade, largely a pedestrian public space that is linked to other open and green spaces, historic sites, and especially designed buildings for special purposes creating a clear and legible pedestrian network. Parks and gardens, even floating ones on the river (on barges), should be part of that network. Various public programs — cultural, informational and recreational — could be designed for some of those areas.

Vitality of a river

It is also obvious that to have riverbanks, one needs to have a river. The dynamicity of the river, along with its canals (whichever are remaining), should be recovered and maintained by obliterating adverse features and modifying some of the existing conditions (a drive that is now ongoing). The latter may include radical changes and relocations of some current operations in the area, including the ill-organised and deeply debilitating IWTA terminal. A renewed vitality can be engineered by introducing a new set of economic activities. If Pahela Baishakh can be invented into a cultural phenomenon that defines modern Dhaka, why cannot certain activities be resuscitated that represent the old tradition of the city. We foresee dynamic activities on and along the river through the systematic promotion of boat racing, water pageants, floating restaurants and various tourism related enterprises.

Revitalised Sadarghat as an economic engine

A re-planned and reconstituted Sadarghat can be a more powerful economic engine than the ramshackle bazaar and ad hoc economy it thrives on now. There’s no denying that there is an active economy in the area but it is haphazard and myopic, and often stands in contradiction to a larger public good. The new economic benefit deriving from a reorganisation will not only be for the people of the area but for the whole city. The economic turn should be a way to motivate the citizens and stakeholders of the area in participating in a renewal program. With a re-planned Sadarghat, the economic life of the area could be revitalised manifold through new commercial generators, such as well-planned shops and markets, business centres, hotels, restaurants, eateries and other enterprises, including large scale cultural and entertainment centres (rather than the lakri and daab stores, chhapras and hovels lining the river now). All these could create a tourist potential that in turn will generate a new economic bonanza.

New and modern business centres in specific locations, perhaps as tall buildings, could be conceived catering to the vibrant economy of the old city.

Traffic and movement

Traffic through and to Sadarghat is key to a sustainable future. At present, chaos is a synonym for traffic, and even that would be an understatement. New modes of access to and from Sadarghat linking critical points in the city will have to be created. It can be through modest (but creative) rearrangement of existing road and traffic movements, or a little bolder plan of river connections (such as connecting Tongi Bridge to Naryanganj in a river bus and taxi system), and perhaps a light rail link that could be conceived over the embankment encircling Dhaka. Land traffic should be linked to river buses at strategic stops on the banks. Such nodes could be developed as centres of new planned activities. Pedestrian and vehicular traffic along the riverbank should be carefully segregated so that there is mostly uninterrupted pedestrian movement. The current flood protection wall built above the existing street level gives a cue to build an elevated walkway or promenade above the wall.The lower level could be used as vehicular road, car park, or some commercial functions.

A riverbank language

Architectural and spatial types need to be innovated that are appropriate for a riverbank urban experience. The architectural and civic assets already existing in the district can be enhanced and used as loci of new activities. The Ahsan Manzil area, for example, should be maintained as a civic place with the current museum as the focal point, but with better connections to the city. Ali Mia’s Talao, a most unique development around a water tank, is another urban treasure that now lies completely inaccessible and unrecognised. The new design for the riverbanks could establish links to such significant locations making a new and clearly designated network of urban spaces. The potential of some existing cultural nodes, such as Bulbul Academy, could be heightened and used to inject new cultural dynamics to the area. The move to make Shakhari Bazar a heritage neighbourhood could also be linked to the district. Such a clear composition of spaces, streets and buildings, connecting the historic and the new, the city and the river, could serve as destinations for both local people and visiting tourists.

Strategies

How to go about doing this? We further suggest:

1. A new authority as the Buriganga Riverbank Authority empowered to maintain the mission of the new riverfront district. The Authority could have its own management and policing force to ensure proper functioning of the area, and stop encroachment and illegal building, and river pollution. Prior to the formation of the Authority, an Urban Task Force could be set up by the government to study the scope and potential of such a district.

2. Split the scope of the terminal and relocate it at other locations. The terminal building may be shifted wholesale to other accessible point or split into two with each terminal dedicated to upriver and downriver direction (a new terminal near Tongi Bridge is possible even if that means dredging the river for a north and south linkage). The new terminal could be a loci for new planned development and activity in that region.

3. Make government, city and private partnerships in the new economic ventures. This could be advanced by government advocacy with exemplary moves and promotions.

4. A “selective surgery” will have to be initiated whereby certain buildings in the area are retained, and certain others are removed or transformed. Pockets of urban spaces, large or small, designated or hidden, will have to be recovered and organised and linked to the identifiable pedestrian system.

5. The development of Sadarghat must also take into account the opposite bank. To bring certain symmetry, a sequence of activities and projects with appropriate traffic links may be initiated in the opposite bank which could be part of the Riverfront District. For example, the old “dock” area can be reconverted as an exemplary site for a convention centre with hotel and housing with parks, gardens, vertical farms, etc., or a large-scale recreational centre with stadium and other sport facilities. All these can spark off new development energy in the area.

Written by Kazi Khaleed Ashraf

Published on Volume 3, Issue 7 of Forum, a monthly publication of The Daily Star, on July 2009.

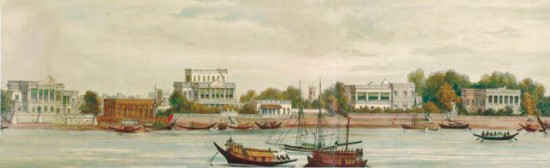

Images for the article were created by Masudul Islam following suggestions by Salauddin Ahmed and Kazi Khaleed Ashraf.